1) Read the Stem Like a Clinician: Find the Pivot, Not Every Detail

Step 2 CK vignettes look long because they compress a patient’s timeline, differential, and next-step decision into ~90 seconds of reading and reasoning. Your goal is not to memorize every sentence; it’s to surface the pivot findings that determine the decision pathway. Pivots are the small set of data points that either confirm a critical branch (e.g., “hemodynamic instability,” “pregnancy,” “immunosuppressed,” “fever after delivery,” “acute chest pain with diaphoresis”) or rule out unsafe options (e.g., “sulfa allergy,” “prolonged QT,” “G6PD deficiency”). When you train your eye to spot pivots, the rest of the stem becomes context rather than clutter.

Read in two passes. Pass A (10–15 seconds): skim the last line and the beginning of the options to learn the task (“best initial test,” “most accurate test,” “next best step,” “most appropriate management,” “counsel the parent”). Then skim the opening demographics and chief complaint for high-yield qualifiers (age, sex, pregnant/postpartum, immunocompromised). Pass B (35–45 seconds): scan for pivots: onset/timing, severity, red flags, vitals, pregnancy status, meds, devices, exposures, and exam features that force an algorithmic fork (meningismus, peritoneal signs, focal neurologic deficits, ST-elevation equivalents, late decelerations, nuchal rigidity, pulsus paradoxus, saddle anesthesia).

Tag each pivot mentally with the clinical axis it controls: resuscitate vs. diagnose first; isolate vs. evaluate; treat now vs. watchful waiting; image vs. lab vs. no test; inpatient vs. outpatient. Most vignettes hide one dominant axis—find it quickly and you’ll often eliminate half the options before calculating anything. As you read, ignore ornamental details that don’t change the axis (e.g., pet ownership in classic ACS, or ethnic heuristics that aren’t tied to prevalence-sensitive differentials). Focus instead on discriminators that change the answer if absent or present.

Finally, build a habit of premortem thinking: ask, “If I choose option X, what must be true in the stem to make that safe?” That question automatically seeks pivots (pregnancy, anticoagulation, renal function, hemodynamics) and protects you from attractive-but-unsafe distractors. Vignette reading becomes faster when you stop collecting facts and start confirming requirements. On Step 2 CK, the right answer is almost always the one safest for the patient right now given the pivots you identified.

2) A Four-Step Vignette Algorithm: From Clues → Branch → Rule-Outs → Single Best Answer

The Single Best Answer (SBA) format rewards a disciplined, reproducible approach. Use this four-step algorithm on every stem:

- Clarify the task. Label the question type before reading deeply: “best initial test,” “most accurate test,” “next best step in management,” “most likely diagnosis,” “counseling/ethics.” Each task has a different default priority (e.g., stabilization outranks diagnostic yield for “next step” when unstable).

- Extract pivots to choose the branch. Decide the clinical axis (stabilize first vs. test first; treat empirically vs. confirmatory testing; isolate vs. image; admit vs. outpatient). Force yourself to articulate the branch (“Unstable sepsis → fluids/pressors before CT”; “Pregnant with RLQ pain → graded compression ultrasound first; avoid ionizing radiation unless benefits outweigh risk”).

- Eliminate with safety and sufficiency. Strike options that are unsafe given the pivots (e.g., beta-blockers in cocaine chest pain, warfarin in pregnancy, CT with contrast in anaphylaxis history without premedication context). Next, remove insufficient answers—choices that might be reasonable eventually but don’t answer the question at the current step (e.g., ordering a colonoscopy when the task is “best initial test” for acute lower GI bleeding in an unstable patient).

- Select the most defensible single action. Among the surviving options, pick the one that directly addresses the primary problem with the highest safety and yield per time. If two seem similar (e.g., “ABG” vs. “pulse oximetry”), choose the one that most efficiently informs management at the current step. When two tests confirm the same diagnosis, the “most accurate test” is the gold standard (e.g., biopsy) while the “best initial test” is the fastest, least invasive, and sufficient to move care forward (e.g., noninvasive imaging).

Make the algorithm muscle memory by narration during practice: “Task?—next step. Branch?—hemodynamically unstable → stabilize. Unsafe?—NSAIDs contraindicated in pregnancy. Sufficient?—portable CXR answers the immediate question.” Repetition conditions your eye to see the exam’s internal logic, not just the medical content.

3) “Best Initial Test” vs. “Most Accurate Test” vs. “Next Best Step”

Many misses on Step 2 CK come from mixing up what the exam is asking rather than not knowing medicine. Align your answer with the decision tier:

| Decision Tier | What It Means | Default Preference | Example Contrast |

| Best initial test | First diagnostic step that is fast, accessible, low risk, and likely to change immediate management. | Noninvasive, high-yield, rules in/out dangerous diagnoses quickly. | Suspected PE but stable: D-dimer (low pretest) or CTPA (moderate–high) vs. pulmonary angiography. |

| Most accurate test | Gold standard with the highest sensitivity/specificity independent of feasibility. | May be invasive or slower; not necessarily the first step. | Hemochromatosis: liver biopsy (most accurate) vs. TSAT/ferritin + HFE testing (initial). |

| Next best step | Immediate action that moves care forward given current data—often management rather than testing. | Stabilize first if unstable; treat when diagnosis is clear enough. | STEMI with shock: emergent revascularization/pressors before detailed risk stratification. |

When in doubt, ask: “What is the time cost of being wrong at this tier?” The higher the risk of harm, the more the exam expects stabilization or narrow, high-yield testing before complex diagnostics. Conversely, when the patient is stable and the differential is broad, the “best initial test” tends to be the least invasive discriminator that collapses multiple diagnoses at once (e.g., ultrasound for RUQ pain, TSH for suspected hypothyroidism with nonspecific symptoms, urinalysis for dysuria).

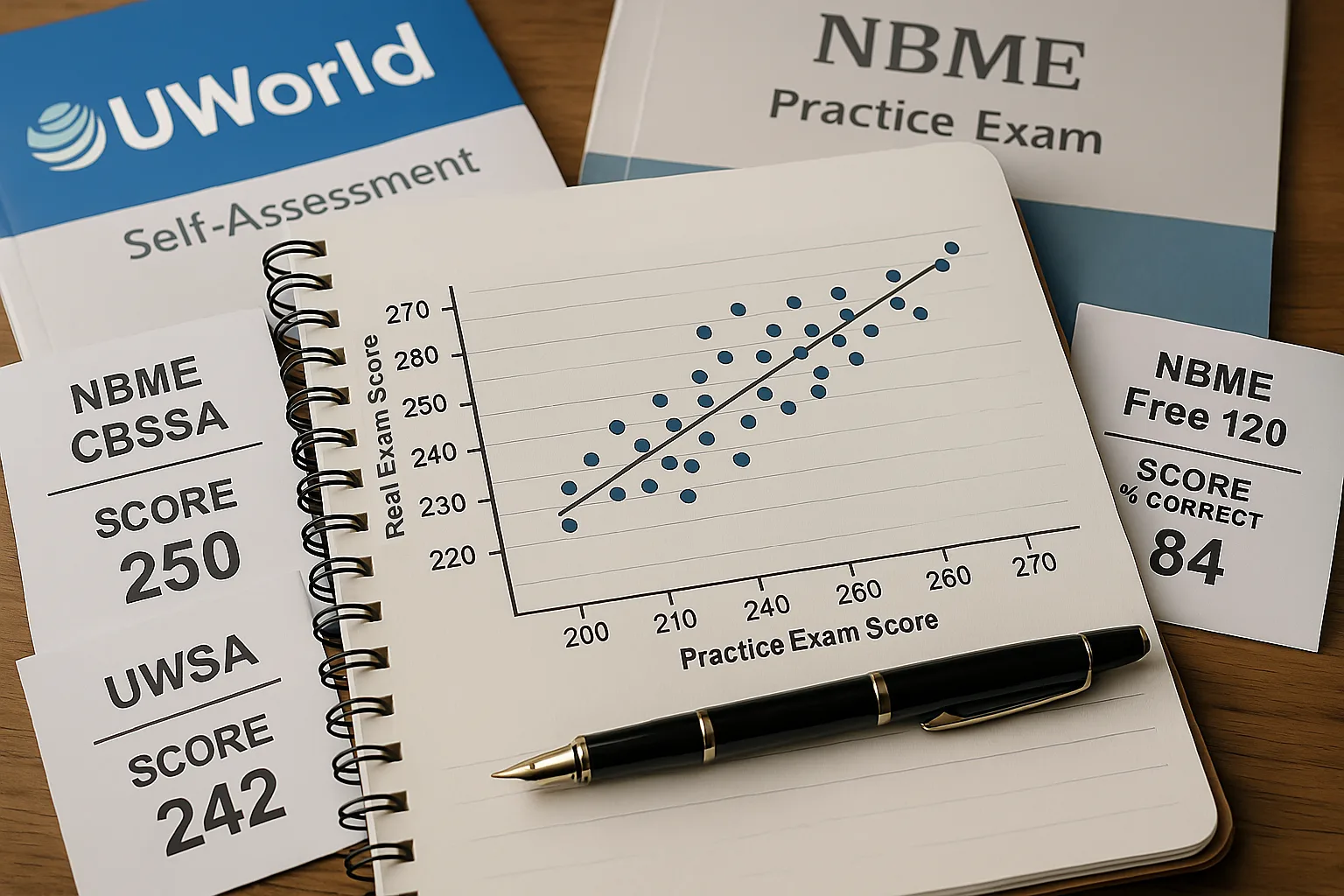

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

4) Stabilize First: The ED/Wards Logic the Exam Expects

On the wards, you treat the patient in front of you, not the differential in your head. Step 2 CK mirrors this ethic. If a vignette signals physiologic threat—airway compromise, hypoxia, hypotension, arrhythmia, active bleeding, altered mental status with airway risk—the safest answer is almost always a stabilization move before diagnostic depth. Think in ABCDE: airway positioning and adjuncts; oxygenation/ventilation; IV access and fluids/blood; pressors if indicated; early empiric therapy for time-sensitive killers (antibiotics for sepsis, aspirin and antithrombotics for STEMI when appropriate, magnesium for torsades, intramuscular epinephrine for anaphylaxis).

Stabilization does not mean random action—it means targeted moves anchored to the pivot findings. For example, “fever + hypotension + high lactate” → fluids, cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and source control; the CT scan comes after blood pressure and oxygenation are addressed. “Third-trimester vaginal bleeding with nonreassuring fetal heart tracing” → stabilize mother, continuous monitoring, call obstetrics; do not send the patient to prolonged imaging. “Severe asthma with silent chest and rising CO2” → escalate bronchodilators and steroids, consider ventilatory support early; do not delay for chest CT.

When stems are crafted to trap you, the wrong answers are typically seductively specific (“order MRI with gadolinium…”) while the right answer is operational and immediate (“secure the airway,” “start broad antibiotics,” “administer magnesium sulfate,” “urgent OB evaluation”). If you hesitate, ask: “Would a responsible internist change this patient’s trajectory now with this action?” If yes, it’s probably correct. If it merely refines the diagnosis without altering the immediate risk, it’s probably wrong at this step.

5) Probability & Yield: Using Pretest Thinking Without the Math

Step 2 CK rarely asks you to compute likelihood ratios, but the stems reward intuitive pretest reasoning. When your pretest probability is very low, a positive test is more likely to be a false positive; when it’s very high, a negative test often doesn’t move the needle. Translate this into practical exam heuristics: in low-risk, PERC-negative chest pain without red flags, skip imaging; in classic cellulitis without systemic toxicity, don’t order blood cultures; in classic uncomplicated cystitis, treat empirically rather than reflexively imaging or sending extensive labs.

Use tests that either change management or compress the differential. Choose single tests that carve away entire branches (e.g., ultrasound in suspected biliary disease; D-dimer to rule out VTE in low-risk patients; BNP to separate cardiac from noncardiac dyspnea when the exam wants an initial discriminator). Avoid ordering narrow, expensive, or invasive tests when a broader, safer discriminator exists at the same step.

Time also drives probability. In acute conditions, the exam prioritizes decisions that prevent deterioration while information accumulates: start antibiotics for febrile neutropenia, give steroids for suspected temporal arteritis with vision symptoms, give anti-D immunoglobulin after Rh-incompatible exposure. Conversely, when harm from treatment is meaningful and the patient is stable (e.g., long-term anticoagulation, major surgery), the exam pushes you toward confirmatory testing or additional staging before committing.

Finally, beware of base-rate neglect distractors. A rare diagnosis with a flashy symptom cluster is seldom correct when a common diagnosis fits all the data. When a common disease explains everything, it’s usually the answer—unless the stem is screaming a red flag (toxicity, instability, epidemiologic exposure) that demands otherwise.

6) Distractor Taxonomy: How the Exam Tries to Mislead—and How to Answer Safely

Most wrong answers fall into predictable families. Naming the family makes them easier to reject quickly. Use this compact taxonomy while reviewing blocks:

| Distractor Type | What It Looks Like | Anti-dote (Safe Response) |

| Premature sophistication | Fancy test before stabilizing basics (angiography, MRI with contrast, rare serology). | Stabilize first; pick the lowest-risk discriminator that changes management now. |

| Tempting completeness | Ordering “everything” to be thorough. | Choose the single action that advances care; avoid shotgun panels. |

| Step mismatch | Gold standard when the stem asks for “best initial,” or vice versa. | Map the task to the tier (initial vs. most accurate vs. next step). |

| Unsafe in context | Drug or procedure contraindicated by a pivot (pregnancy, QT prolongation, G6PD, anticoagulation). | Re-scan for pivots; eliminate anything inconsistent with safety constraints. |

| False urgency | Diagnostic detour framed as emergent without instability. | If stable, discriminate first; if unstable, treat first. |

During review, label each miss with its distractor family and write the counter-move you should have applied. Over time, you’ll develop reflexes: “This looks like premature sophistication—choose fluids/antibiotics, not CT angiography,” or “This is a step mismatch—the exam wants the first test, not the gold standard.” That reflex saves minutes and points across an 8-block day.

7) Block Mechanics, Timing, and Flagging: How to Finish Strong

Plan to solve ~40 items per 60-minute block with a steady cadence: ~30–40 seconds for Pass A (task + demographics + last line/options scan), ~40–50 seconds to extract pivots and pick a provisional answer, and a short final check only when two choices remain. Over-review is a bigger risk than under-review; changing correct answers to wrong ones commonly occurs when you revisit without new information.

Flag intelligently. Flag only when: (1) you misread a number/name and want to confirm, (2) two choices remain after a full algorithmic attempt, or (3) you suspect a contraindication you need to re-verify. Avoid generic flagging “just to look again”—you will not have time. In the last 4–5 minutes, sweep flagged items in rapid triage: eliminate unsafe options, prefer actions that immediately change care, and commit.

Break strategy matters. Treat breaks like glucose infusions for your frontal lobe: short and frequent beats one long crash. Hydrate, use light snacks, and time bathroom trips to avoid entering a block distracted. Many examinees perform best with a front-loaded short break after Block 1 to settle nerves, then mid-day and late-day brief resets. Use your practice blocks to test your personal schedule and lock it in before test day.

Interface hygiene. Use highlight/scratch-pad tools to mark pivots (e.g., “postpartum day 3,” “hypotensive,” “new murmur,” “on warfarin”). When audio or media is present, read the stem before playing the clip to avoid anchoring on a single finding. If a question is salvageable by recognizing a safety rule (“never send an unstable patient to CT”), commit to the safe action and move on.

Above all, protect pace by trusting your process. The exam rewards consistent, safe reasoning more than heroic flashes of brilliance on a few items.

8) Rapid-Review Checklist & “Phrases That Score”

Rapid-Review Checklist

- Task first: Identify whether it’s diagnosis, initial test, most accurate test, immediate management, or counseling.

- Pivots: Hemodynamics, pregnancy, immunosuppression, red flags, exposures, meds/allergies, timing.

- Branch: Stabilize vs. test; treat now vs. confirm; isolate vs. evaluate; admit vs. outpatient.

- Safety screen: Remove contraindicated options (pregnancy, QT, G6PD, anticoagulation, renal/hepatic failure).

- Sufficiency check: Prefer the single action that advances care at the current step.

- Probability sense: Favor common diagnoses unless a red flag forces otherwise.

- Flagging rule: Only when two remain or a specific fact needs verification.

- Breaks: Plan short, regular resets; practice the exact schedule beforehand.

Phrases That Steer You Correctly

- “Unstable → stabilize before diagnostics.”

- “Best initial ≠ most accurate.”

- “Choose the action that most directly changes care now.”

- “If it’s unsafe in pregnancy/anticoagulation/QT/G6PD, eliminate.”

- “When two tests answer the same question, pick the one with lower risk and faster impact.”

- “Do not exhaustively test when a clear, safe treatment is already indicated.”

- “When evidence is equivocal, pick the option that maximizes patient safety.”

How to use this playbook: verbalize the four-step algorithm during every practice block for one week, label each miss with its distractor family, and rehearse your break plan during full-length simulations. Consistency wins Step 2 CK.

References & Further Reading

100+ new students last month.