What Step 1 Really Tests—and Why Questions Are the Backbone

Step 1 is a one-day, computer-based exam delivered in seven 60-minute blocks across an eight-hour session. Each block has up to 40 items; the total item count does not exceed 280. Knowing this structure matters because it dictates your pacing, stamina goals, and the size of your daily practice sets. Most importantly, Step 1 evaluates whether you can apply foundational science to clinical contexts—biochemistry, physiology, pathology, microbiology, immunology, pharmacology, genetics, and biostatistics framed through patient vignettes. A blueprint-first perspective ensures your study time maps to what is actually tested, not just what feels comfortable to review.

Because the exam is application-heavy, passive rereading is insufficient. Retrieval practice (producing the answer from memory) drives durable learning and mirrors the mental operations required during the exam. High-quality multiple-choice questions compress this process: they force hypothesis generation, mechanism-level reasoning, and distractor triage under time pressure. Done correctly, question blocks are not just “assessment” but the core of learning. After each block, the post-hoc analysis is where most gains occur: you reconstruct the causal chain (e.g., mutation → protein dysfunction → cellular phenotype → organ-level physiology → clinical findings), verify why each distractor is wrong, and capture portable takeaways into your review system.

Practically, the backbone of a Step 1 plan should be mixed, timed blocks that reflect the integrated blueprint. Reserve content review to clarify mechanisms exposed by your misses, not as an endless prelude to “starting questions.” Your planning target is daily exposure to full-length blocks, with progressive escalation of mixed disciplines to build transfer—physiology to pathology, micro to pharm, and biostats across systems. This approach simultaneously builds knowledge, pattern recognition, and the executive control needed to maintain accuracy while fatigued.

Finally, remember that Step 1 now reports as Pass/Fail; readiness hinges on consistent performance in realistic conditions rather than chasing a particular three-digit threshold. Objective calibration with official resources (see Sections 6–7) ensures your practice curve aligns with exam-day expectations and break-time rules.

2) Choosing—and Using—Qbanks Strategically

Pick a primary question bank and commit to finishing it; add a secondary bank only if time and cognitive bandwidth allow. Your selection should balance realism of stems, mechanistic depth of explanations, interface usability, and tools that accelerate feedback (cross-links, notes, highlights). Regardless of brand, your technique matters more than the logo on the header.

| Qbank | Question Style | Explanations | Best Use | Notes |

| UWorld | NBME-like, mechanism-dense | Deep pathophys + distractor deconstruction | Primary bank; timed mixed blocks | High cognitive load; schedule recovery time |

| AMBOSS | Integrated, concise stems | Tiered depth; on-demand library links | Supplemental drilling; rapid clarifications | Great for targeted weak-area sprints |

| Kaplan (Step 1) | Concept-focused, varied difficulty | Didactic review of basics | On-ramp before heavier banks | Useful during pre-dedicated |

Evidence-based technique. Run most blocks in timed mode with mixed subjects to build discrimination and interleaving (see Section 3). Use “tutor” mode surgically when first learning an especially error-prone topic (e.g., glycogen storage disorders). During review, interrogate each question with four prompts: (1) What was the decisive clue? (2) Which mechanism explains the finding? (3) Why is each distractor wrong? (4) What 1–2 rules can I reuse? Store those rules in a personal error log or spaced-repetition deck, and tag them to blueprint categories (e.g., “renal physiology—transporters”).

Block hygiene. Standardize pre-block checklists (timers off phone, water available, scratch board ready). Post-block, cap review windows (e.g., 2–3 minutes per item) to prevent “explanation grazing.” When patterns emerge (e.g., missing graph questions, conflating Gram-negative rods), create a focused micro-cycle: 20–30 dedicated questions + 20-minute mechanism review + 10 flashcards, then retest within 48–72 hours.

3) The Mastery Cycle: Retrieval, Spacing, Interleaving, Reflection

Long-term retention depends on retrieval practice, spaced repetition, and interleaving. Retrieval practice—testing yourself rather than rereading—reliably strengthens memory traces and improves delayed performance. For Step 1, daily question blocks and flashcard recall tests operationalize this principle. Spacing your reviews forces reconsolidation when forgetting begins, which is more efficient than massed “cramming.” Interleaving, or mixing topics within a session, enhances discrimination among similar mechanisms (e.g., restrictive vs obstructive spirometry, nephritic vs nephrotic pathophysiology).

Implementing spacing at scale. Use a spaced-repetition tool (e.g., Anki) to capture: (1) decisive clues (e.g., “↑ urinary methylmalonic acid → B12 deficiency”), (2) portable algorithms (e.g., “wide anion gap → check osmolar gap → toxic alcohols vs DKA”), and (3) graph reading heuristics (e.g., “right-shifted O2 curve: ↑temperature, ↑CO2, ↑2,3-BPG”). Keep cards terse and mechanism-anchored. Schedule daily new cards conservatively to avoid review debt.

Interleaving in question blocks. Aim for mixed blocks by default. To integrate interleaving without chaos, alternate the block seed (e.g., “renal-heavy mix” one day, “heme-onc-heavy mix” the next) while preserving blueprint breadth. During review, explicitly contrast look-alikes with a two-column mini-table in your notes: similar features on the left, discriminators on the right.

Reflection & error logs. A lightweight error log outperforms a sprawling diary. For each miss, record mechanism, misstep (e.g., premature closure), rule to generalize, and next check-in date. Close the loop by retesting the same construct within 2–7 days (spacing window). This “test → analyze → encode → retest” loop compounds learning and aligns with high-utility methods recommended by cognitive science reviews.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

4) Blueprint-Anchored Study Plan: From Diagnostic to Daily Execution

Baseline. Start with a diagnostic to map strengths and deficits. If you are early, a 40–80-item mixed block under testing conditions is sufficient to set initial priorities. If you are in the dedicated window, consider an official self-assessment to anchor your starting point (see Section 6). Translate results into mechanism-level tasks (e.g., “RAAS pharmacology,” “Type II hypersensitivity exemplars,” “viral replication families”).

Weekly cadence. Your core unit is the full block. Most students progress with 1–2 mixed blocks per day (timed), post-block analysis, and an evening spaced-repetition session. Layer focused content reviews only to resolve recurring mechanisms; avoid open-ended textbook wandering.

| Phase | Daily Core | Supplement | Goal |

| Weeks −8 to −6 | 1 mixed block (timed) | 60–90 min mech review; 30–45 min spaced cards | Identify patterns; build error log |

| Weeks −6 to −3 | 1–2 mixed blocks (timed) | Targeted micro-cycles on weak themes | Close gaps; lift accuracy under fatigue |

| Weeks −3 to −1 | 2 mixed blocks (timed) | Full-length simulation weekly | Stamina + break strategy; calibrate |

| Final 7 days | 1–2 lighter blocks | Rapid-review lists; sleep discipline | Consolidation; avoid overload |

Metrics that matter. Track rolling 7-day accuracy in timed, mixed conditions and error-category velocity (how quickly repeated misses disappear). Treat single-block swings as noise; focus on trajectory. Pair this with cardio-style stamina metrics (e.g., “accuracy drop from first to second block”) to gauge fatigue tolerance. Schedule two “simulation” days during the final month to test your pacing and break routine.

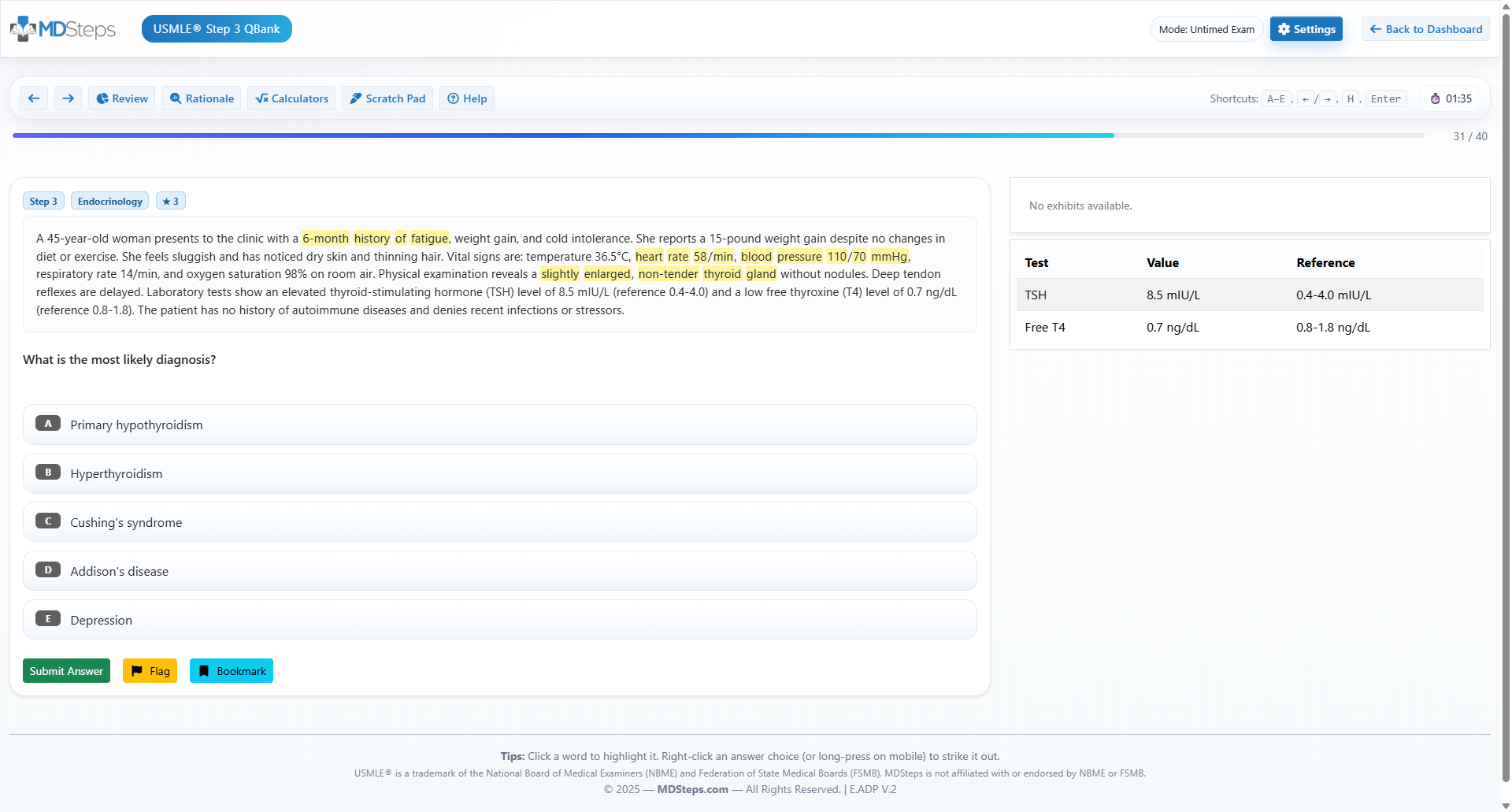

5) Dissecting NBME-Style Questions: A Repeatable Framework

Step-by-step dissection. (1) Skim the last line first to set the task (diagnosis, mechanism, next step, adverse effect). (2) Read the vignette once for signal—age, acuity, exposures, lab signatures, and a single decisive clue (e.g., “↑ methylmalonic acid”). (3) Predict the answer mechanism before seeing options. (4) Scan options quickly and eliminate obvious mismatches. (5) Reconcile data conflicts (e.g., anemia pattern vs reticulocyte count). (6) Choose and commit; do not orbit the same two choices. (7) Post-hoc: articulate why the chosen option must be true and why each distractor cannot be true.

Mechanism anchors. Tie each choice to a mechanistic checkpoint: receptor/second messenger, enzyme/cofactor, transporters, pathology morphology, and biostat formula families. Convert recurring heuristics into flashcards (e.g., “Pseudomonas → oxidase+, non-lactose fermenter, blue-green pigment → antipseudomonal coverage ladder”). Where items include figures/graphs, label axes mentally and verbalize the trend (“sigmoid with left shift → ↑affinity”).

Avoid common cognitive traps. Premature closure (deciding too early) and anchoring (fixating on an early clue) drive many incorrect responses. Counteract by asking “What else must be true if my hypothesis is right?” then seek disconfirming data. For two-step items (diagnosis → treatment, mutation → phenotype), slow down long enough to verify that the second step is logically entailed by the first. During review, map the precise moment your reasoning diverged; this becomes a reusable “anti-error” rule for your log.

Speed without hurry. Your average budget is roughly 72 seconds per item across the day; allocate flex time to dense stems and data-rich images by moving briskly on recognition items. Train this by practicing “first pass commitment”: make a selection when confidence exceeds ~60%, flag borderline cases, and return only if time permits.

6) Calibrating Readiness with Official Resources

Official self-assessments are the cleanest yardstick because they mimic item style and provide scaled feedback. The NBME Comprehensive Basic Science Self-Assessment (CBSSA) offers forms designed specifically for Step 1 preparation. Use one early in dedicated to set the floor, then another ~2–3 weeks out to confirm consolidation under time pressure. Avoid over-testing; you want representative snapshots, not constant disruption of your learning cycle.

The NBME’s interactive orientation and the publicly available “Free 120” sample questions are also valuable, especially to normalize the interface and test-center workflow. Run at least one session on the official platform, in a quiet setting, timed, with breaks structured exactly as you plan for exam day. Track not only accuracy but also pacing, confidence decay across a block, and the recovery effect after a short break.

Interpreting results. Because Step 1 is reported as Pass/Fail, focus on pattern stability across mixed blocks and your trajectory on official forms. Combine CBSSA results with your rolling Qbank accuracy in timed, mixed conditions. If performance is borderline, execute a targeted 10–14-day micro-plan (two weak systems + a universal domain like biostatistics) and repeat a shorter, high-fidelity check (e.g., a fresh mixed block on a simulation day). Remember: calibration is about decision-readiness, not chasing an artificial number.

7) Stamina, Pacing, and Exam-Day Mechanics

Step 1 grants 45 minutes of break time across the day, plus any time saved by finishing blocks early; many examinees also gain extra break minutes by skipping the tutorial after practicing it at home. Decide your break structure in advance (e.g., short “micro-breaks” after Blocks 1–2, a longer refuel after Block 4, and a final short reset before the last block). Eat familiar, low-glycemic snacks and hydrate modestly to avoid physiologic distractions.

Pacing. Train to an average of ~72 seconds per question across the day. Build a per-block rhythm: first pass to 40 with firm commitments and flags, then a timed second pass for flagged items. Avoid time-sink spirals by enforcing a 90-second hard cap on any single revisit. Practice this cadence during two full-length simulations in the final month (seven 60-minute blocks, realistic breaks) to inoculate against decision fatigue.

Test-center workflow. The Prometric environment is predictable but strict. Rehearse check-in logistics, permitted items, locker use, and ID requirements. Use the on-screen highlighting/strikethrough tools judiciously; they help externalize working memory without clutter. When anxiety spikes, box-breathe for 20–30 seconds, then articulate the stem task and decisive clue out loud in your head before re-engaging the options. Post-block, mentally “close the tab” to prevent emotional carry-over.

Contingencies. If you hit an unexpectedly hard block, ensure adequate calories/hydration during the next break and reduce cognitive friction by writing a two-line reminder on your laminated board: “Task → mechanism → eliminate.” If a tech issue arises, notify staff immediately; do not attempt to troubleshoot on your own.

8) Two-Week Consolidation & Rapid-Review Checklist

Days −14 to −8. Prioritize closure of recurring error themes: choose 2–3 weak systems and a universal domain (biostatistics/ethics) and run daily micro-cycles (20–30 targeted questions → 20-minute mechanism review → 10 flashcards). Maintain one mixed timed block per day for transfer. Keep evenings for spaced cards only; avoid late-night deep dives.

Days −7 to −4. Execute one full-length simulation (seven blocks) using your exact break plan. The following day should be active recovery: light cards, a 40-item block at most, movement, and sleep protection. Translate simulation misses into 10–15 concise, mechanism-anchored flashcards. Review the official interface again so the test center feels familiar.

Days −3 to −1. Taper cognitive load: one lighter mixed block daily, aggressive card pruning, and brief targeted reviews. Confirm logistics (ID, scheduling permit, route, snacks). Night before: no heavy studying; assemble exam-day kit and enforce sleep routine.

Rapid-Review Checklist (bring this to dedicated):

- Run mixed, timed blocks daily; review with a four-prompt script (decisive clue, mechanism, distractors, reusable rule).

- Maintain a compact error log and convert lessons to spaced cards; review cards every evening.

- Interleave systems; explicitly contrast look-alikes in two-column notes.

- Schedule two full-length simulations; rehearse the exact break plan and interface workflow.

- Use official NBME tools (CBSSA, orientation/Free 120) to calibrate and normalize test-day feel.

- Protect sleep, nutrition, and pacing discipline; treat single-block swings as noise—focus on trajectory.

References & Official Resources

100+ new students last month.