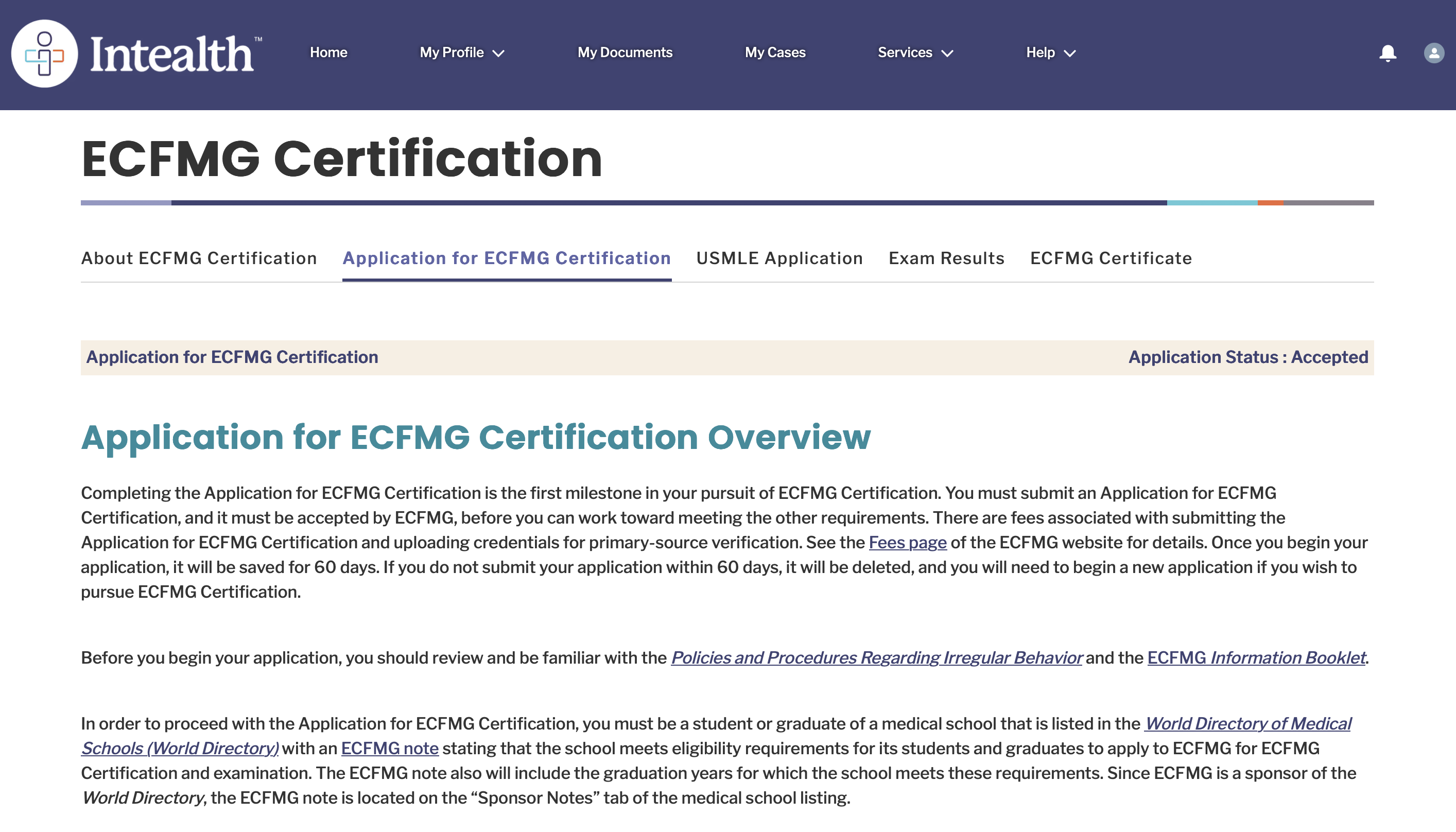

Cognitive biases are predictable thinking errors that quietly distort judgment, especially under the precise conditions of USMLE testing: time pressure, fatigue, pattern overload, and emotional investment. Across Step 1, Step 2 CK, and Step 3, students routinely misdiagnose vignettes, misread question stems, or overvalue irrelevant clues because the brain defaults to shortcuts instead of structured clinical reasoning. This article explores how these distortions emerge, how they differ by exam level, and how to systematically correct them. Bias is not a sign of weak knowledge. It reflects the brain’s reliance on heuristics designed for speed, not accuracy. For example, when a Step 2 CK vignette opens with “a 72-year-old man with a history of smoking presents with back pain,” students quickly anchor on malignancy, often ignoring features of vascular disease. On Step 1, subtle biochemical distractors trigger availability bias when the student recognizes a pathway from a recent Anki card. Step 3’s multistep cases amplify premature closure—students jump to a diagnosis and “treat” it without verifying basics such as vitals or ABCs. The goal is not to eliminate cognitive bias but to recognize when it is likely to appear and consciously intervene with structured mental routines. MDSteps’ analytics dashboard often shows students a pattern: they miss questions not from lack of content knowledge but from predictable decision-making errors. By understanding these mechanisms, identifying triggers, and applying corrective micro-habits, you transform how your brain approaches vignettes. Anchoring bias occurs when the initial detail in a question stem becomes the dominant driver of your interpretation. On USMLE exams, writers deliberately open with emotionally charged or familiar details—age, past medical history, or a dramatic symptom. Students lock onto it, interpret the entire vignette through that lens, and fail to update when contradictory information emerges. Step 1 patterns: Anchoring typically appears in pathophysiology items. A student sees “alcohol use” and prematurely picks alcoholic hepatitis despite lab values pointing toward ischemic hepatopathy. The early clue feels “loud,” and the subsequent data is filtered rather than analyzed. Step 2 CK patterns: In clinical reasoning questions, a student sees “chest pain” and instantly categorizes the question as ACS, overlooking sharp pleuritic pain and decreased breath sounds that point toward pneumothorax. Anchoring here bypasses differential generation entirely. Step 3 patterns: Anchoring commonly leads to treating the wrong diagnosis first in CCS cases. A patient with fever triggers early anchoring on infection, causing the student to order broad-spectrum antibiotics before stabilizing vitals. Fixing it: Use the “last-line-first” technique. Read the actual question task (e.g., “most likely diagnosis,” “next best step”) before reading the stem. This prevents the first sentence from defining your mental model prematurely. Then deliberately identify at least one fact that contradicts your assumed diagnosis. This single move dramatically reduces anchoring errors. Availability bias occurs when your brain retrieves the most recent or vivid information, assuming it must be relevant. For USMLE students, this is amplified by high-volume studying, multiple QBank sessions, and exposure to clusters of similar questions. How it appears on Step 1: After a week of immunology prep, students over-diagnose immunodeficiency disorders in simple recurrent infections. Availability makes the highly studied material seem disproportionately represented. Exam writers exploit this by including superficially similar distractors (e.g., Bruton's vs. transient hypogammaglobulinemia). On Step 2 CK: Rotations influence this bias. A student on OB/GYN sees pregnancy-related pathology in any female under 55. A student on surgery perceives acute abdomen in vague abdominal pain cases. The diagnostic landscape becomes skewed by clinical exposure rather than exam epidemiology. On Step 3: Availability surfaces when students recall recent CCS sequences and try to force identical order sets onto new cases. The danger is assuming similar vignettes require identical management, even when small details change the priority (e.g., trauma ABCs vs. septic shock resuscitation). Fixing it: Apply the “base rate check.” Before choosing an answer, ask: “Does this diagnosis fit epidemiologically for this patient’s age, risk factors, and time course?” The most available diagnosis in your memory often violates base-rate probability. MDSteps’ adaptive QBank intentionally varies likelihood frequencies to train students out of availability-driven decision errors. Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data. Premature closure—deciding too early—is the most common cause of errors across all three Steps. It arises when the brain latches onto the first plausible diagnosis and stops processing new information. On exam day, this manifests as skipping subtle clues, ignoring labs, or misinterpreting which symptom actually defines the case. Step 1 version: Students see a classic presentation for DKA, stop reading, and miss the fact that the child is actually hypoglycemic from an insulin overdose—flipping management entirely. Classic buzzwords are weaponized to tempt premature closure. Step 2 CK version: A patient with dyspnea is quickly categorized as heart failure, but the vignette includes recent immobilization, unilateral leg swelling, and pleuritic pain—clear hints of PE. Because the initial hypothesis feels strong, contradictory data is dismissed. Step 3 version: In CCS, premature closure leads to wrong orders. Students treat the presumed diagnosis instead of identifying immediate threats. For example, presuming CHF and ordering diuretics in a hypotensive patient worsens outcomes. Step 3 heavily penalizes this bias. Fixing it: Use the “3-bucket method”: If Buckets B or C contain meaningful clues, you are closing too early. This technique forces a more careful re-evaluation and dramatically improves accuracy. Representativeness bias occurs when you expect a disease to look like its “classic” teaching-case version. USMLE stems frequently hide the diagnosis beneath atypical or subtle presentations. Students anchored to prototypes miss these nuanced variants. Common Step 1 example: Students expect iron-deficiency anemia to show microcytosis. Early cases often present as normocytic anemia. Representativeness prevents recognizing early pathophysiology. Step 2 CK example: Elderly patients rarely present with textbook symptoms—no fever in sepsis, no chest pain in MI. Students expecting classic findings underestimate subtle presentations. Step 3 example: Representativeness leads to missing dangerous atypical presentations, such as a painless aortic dissection in diabetics. Step 3’s emphasis on real-world variability makes this bias especially harmful. Fixing it: Replace “classic pattern recognition” with “pattern range recognition.” For each disease, know its mild, atypical, pediatric, geriatric, and comorbidity-modified forms. MDSteps’ QBank includes variable presentations within each disease category precisely for this reason. Confirmation bias makes you selectively notice clues that strengthen your chosen hypothesis while ignoring contradictory data. USMLE stems often contain one misleading feature that tempts you down the wrong diagnostic path. Step 1 example: A question suggests hyperthyroidism, and the student then interprets tachycardia and weight loss as confirmation—while the presence of high TSH (central hypothyroidism) is misread as a typo. Step 2 CK example: A student suspects pneumonia and overinterprets crackles while ignoring signs of pulmonary edema that shift the diagnosis toward heart failure. Step 3 example: In CCS, confirmation bias causes students to keep ordering tests to “prove” their diagnosis instead of moving to treatment, wasting time and incurring penalties. Fixing it: Build a habit of actively searching for disconfirming evidence. After forming an initial impression, ask: “What would make this diagnosis impossible?” This subtle reframing dismantles confirmation bias more effectively than simply re-reading the question. The most reliable way to neutralize bias is to automate a consistent, disciplined review system. Here is a simplified 5-step method used by high-scoring examinees: This prevents anchoring and clarifies the task before the narrative shapes interpretation. Extract objective anchors: vitals, labs, timeline, red flags. These trump emotional or vivid clues. Before selecting an answer, articulate at least two plausible diagnoses. This disrupts premature closure and availability bias. Identify clues that do not fit your leading diagnosis. They are often the key to the correct answer. In CCS, apply a strict ABCDE check before interpreting cause or ordering diagnostic studies. This alone eliminates a majority of cognitive errors at this level. MDSteps’ adaptive QBank reinforces this workflow by analyzing errors, showing whether content gaps or reasoning flaws drove each miss, and auto-generating flashcards from your incorrect answers for spaced repetition. To master cognitive bias management, incorporate timed mixed blocks into your study schedule and review not only what you missed but why you chose the wrong answer. MDSteps’ analytics and automatic readiness dashboard provide this breakdown automatically, making it easier to detect patterns and refine your exam reasoning. Medically reviewed by: Sarah Imran, MDWhy Your Brain Falls for Traps on USMLE Exams

Anchoring Bias: When the First Clue Hijacks Your Thinking

Exam Common Anchors Correction Strategy

Step 1

Buzzword pathology, enzyme names, classic triads

Read labs last, identify contradictions

Step 2 CK

Age, PMH, dramatic symptoms

Create two provisional diagnoses before committing

Step 3

Initial symptom framing the case

Run ABCDE checklist before interpreting cause

Availability Bias: When Recent Study Material Masquerades as Truth

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

100+ new students last month.

Premature Closure: The Most Dangerous Error in USMLE Reasoning

Representativeness Error: When the “Classic Case” Misleads You

Confirmation Bias: How You Subconsciously Search for Evidence You Want

A Structured System to Eliminate Bias Across All USMLE Steps

1. Last-line-first reading

2. Landmark identification

3. Two-diagnosis rule

4. Contradictions hunt

5. Stability check for Step 3

Rapid-Review Checklist: Spotting Thinking Errors in Real Time

References

Fixing Your Exam Brain: How to Recognize and Defuse Thinking Errors on Step 1, Step 2 CK, and Step 3.