Understanding the Thyroid Spectrum on Step 2 CK

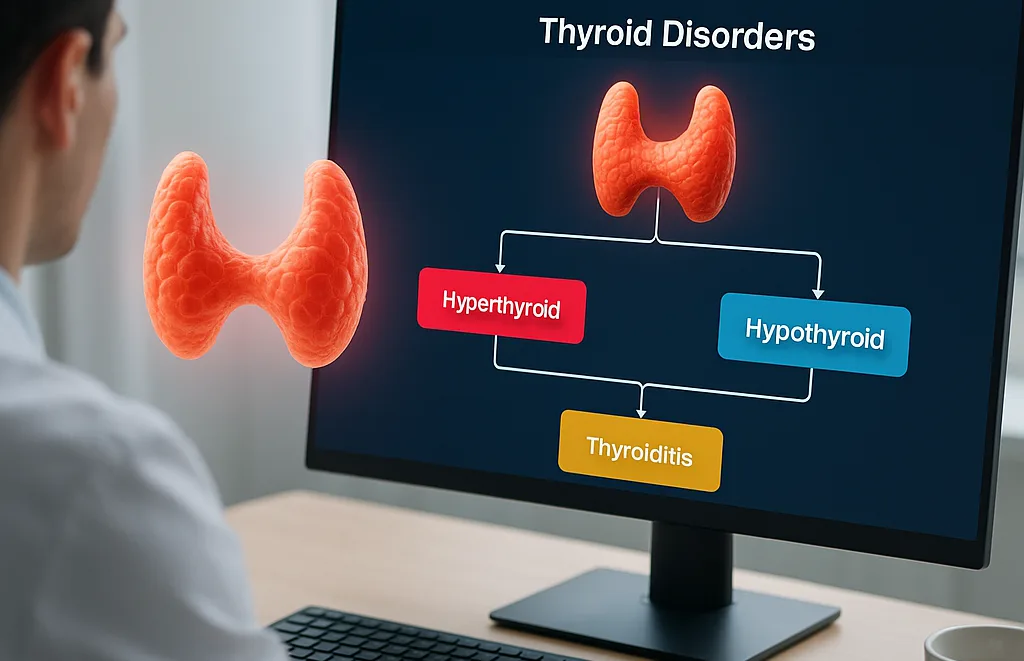

Thyroid disorders appear frequently on Step 2 CK, and most questions hinge on rapid interpretation of TSH and free T4 followed by correct use of a hyperthyroidism vs hypothyroidism algorithm. Within the first 100 words, recognize the core pattern: TSH moves opposite of free T4 unless the pituitary is the problem. Every thyroid question—whether Graves disease, Hashimoto hypothyroidism, postpartum thyroiditis, or central dysfunction—emerges from a structured triage of labs, clinical context, and imaging.

Examinees often make predictable mistakes: anchoring on symptoms, over-emphasizing antibody testing, or ordering radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) at the wrong time. This article builds a complete, exam-focused algorithm that mirrors NBME logic, giving you a consistent framework for all thyroid presentations.

Across eight sections, you’ll learn (1) how to distinguish primary vs secondary causes, (2) the high-yield interpretation of RAIU, (3) what differentiates thyroiditis from true hyperthyroidism, and (4) when treatment must be urgent—such as thyroid storm or myxedema coma. When appropriate, we’ll reference clinical clues like tremor, weight change, menstrual irregularities, or bradycardia to guide pattern recognition.

Throughout the guide, we’ll highlight subtle traps, such as normal free T4 in subclinical disease, falsely elevated T4 from biotin use, or blocked T4-to-T3 conversion in amiodarone patients. We’ll also show how platforms like MDSteps’ Adaptive QBank reinforce these patterns automatically by generating targeted flashcards from your missed questions—an approach that is especially powerful for endocrine memorization.

Core Thyroid Algorithm: Start With TSH, Then Move Downstream

The Step 2 CK approach begins with a two-branch logic tree. If TSH is low, think hyperthyroidism. If TSH is high, think hypothyroidism. If both are abnormal in the same direction, think central disease. The mistake is skipping this sequence—many students begin with antibodies, imaging, or symptoms, all of which can mislead.

| Lab Pattern | Most Likely Etiology | Next Step |

|---|

| ↓TSH, ↑Free T4 | Hyperthyroidism | RAIU or antibodies |

| ↑TSH, ↓Free T4 | Primary hypothyroidism | TPO antibodies |

| ↓TSH, ↓Free T4 | Secondary hypothyroidism | Pituitary evaluation |

| ↑TSH, ↑Free T4 | TSH-secreting adenoma | Pituitary MRI |

This simple matrix captures nearly every thyroid disorder tested on Step 2 CK. The algorithm only expands once the student identifies the main branch. For example, a patient with weight loss, tremor, and a low TSH should not jump to thyroiditis—your next step is determining the mechanism of excess hormone. That means RAIU when safe, or thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) testing when RAIU is contraindicated (pregnancy, breastfeeding).

At this point, the exam often inserts distractors: pregnancy nausea, lab interference from biotin, acute illness causing euthyroid sick syndrome, or medication effects. Recognizing these patterns prevents premature diagnostic closure, one of the most common NBME traps.

Hyperthyroidism Patterns: Graves, Toxic Nodules, and Thyroiditis

Hyperthyroidism on Step 2 CK is primarily categorized by whether the thyroid is overproducing hormone (true hyperthyroidism) or leaking preformed hormone (thyroiditis). RAIU makes this distinction. High uptake means the gland is metabolically active; low uptake signals destructive or inflammatory processes. This decision point is essential because treatments differ dramatically.

Graves disease shows high uptake with a diffuse pattern. Eye findings—lid lag, exophthalmos, or periorbital edema—are classic but not required. Always think autoimmune stimulation via TSI antibodies. In a vignette, look for a young woman with anxiety, palpitations, heat intolerance, and a homogeneous high-uptake scan.

Toxic adenoma reveals focal high uptake, whereas toxic multinodular goiter demonstrates patchy uptake. These patients often have long-standing nodular thyroid disease and fewer autoimmune symptoms. Step 2 CK frequently tests the distinction between these nodular etiologies and Graves because management diverges: radioactive iodine ablation vs methimazole titration.

Thyroiditis (viral, postpartum, drug-induced) produces low RAIU despite clinical hyperthyroidism due to gland destruction. Painful subacute granulomatous (De Quervain) thyroiditis includes a tender thyroid, elevated ESR, and transient hyperthyroidism → hypothyroidism → recovery. Postpartum thyroiditis presents with painless inflammation 1–6 months after delivery and follows a similar triphasic course.

On exam, any hyperthyroid vignette with recent viral illness, pregnancy, or amiodarone exposure should shift you toward a thyroiditis diagnosis rather than Graves. MDSteps’ analytics dashboard helps reinforce these differentiations by tracking how you perform across endocrine categories, highlighting weak nodes in your diagnostic tree.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

Hypothyroidism: Primary, Secondary, and Special Situations

Primary hypothyroidism—driven most commonly by Hashimoto thyroiditis—shows high TSH and low free T4. Symptoms include fatigue, cold intolerance, constipation, menstrual irregularities, weight gain, and bradycardia. Step 2 CK often provides nonspecific symptoms and expects you to anchor your reasoning on labs, not clinical impression.

Autoimmune hypothyroidism (Hashimoto) includes elevated TPO antibodies, and goiter may be present early before atrophy develops. A common NBME trap is conflating postpartum thyroiditis hypothyroidism with Hashimoto—both may show elevated TPO antibodies. The key distinction is the timeline and the preceding hyperthyroid phase in postpartum disease.

Secondary hypothyroidism presents with low TSH and low free T4, typically from pituitary or hypothalamic pathology. These vignettes include amenorrhea, galactorrhea, visual field defects, or adrenal insufficiency. The pitfall: failing to evaluate adrenal status before starting levothyroxine, which can precipitate adrenal crisis.

Sick euthyroid syndrome produces low T3 with normal or low T4 and variable TSH—seen in critical illness. You do not treat it; repeat testing occurs after recovery. The exam likes this scenario because students reflexively treat abnormal numbers instead of the clinical situation.

Thyroiditis Variants and Their Distinctive Clues

Thyroiditis subtypes are differentiated by tenderness, timeline, and RAIU. On Step 2 CK, recognizing these distinctions ensures proper management:

- Subacute (De Quervain) thyroiditis: painful, elevated ESR, low RAIU, transient hyper → hypo → euthyroid.

- Painless / Silent thyroiditis: autoimmune, mild symptoms, low RAIU, no tenderness.

- Postpartum thyroiditis: autoimmune, occurs within 1–6 months of delivery.

- Drug-induced thyroiditis: amiodarone, interferon-alpha, TKIs.

- Radiation-induced thyroiditis: after radioactive iodine therapy.

Management focuses on symptom control: beta-blockers for hyperthyroid symptoms, NSAIDs or steroids for pain, and levothyroxine only if the hypothyroid phase is prolonged or symptomatic. RAIU is low in all forms of thyroiditis, making it a major branch point in the hyperthyroid algorithm.

Management Algorithms: Stabilize → Identify Mechanism → Treat

The NBME consistently follows stabilization-first logic. Hyperthyroid patients with palpitations or tremor must receive beta-blockade immediately. Only after stabilization do you identify etiology and select definitive therapy. Do not jump straight to methimazole without first confirming hyperthyroidism.

For hypothyroidism, treatment is straightforward—levothyroxine—for most patients. Exceptions include secondary hypothyroidism (check cortisol first), pregnancy (higher dosing needed), and older patients or those with coronary disease (slower titration).

| Condition | Immediate Step | Definitive Treatment |

|---|

| Graves | Beta-blocker | Methimazole or RAI ablation |

| Toxic adenoma | Control symptoms | RAI ablation or surgery |

| Thyroiditis | Beta-blocker ± NSAIDs | Supportive |

| Hypothyroidism | None emergent | Levothyroxine |

Common Step 2 CK Pitfalls and NBME Traps

The thyroid domain is rich in distractors. The most frequent exam errors include over-relying on antibodies when initial labs already provide the answer, skipping stabilization in acute hyperthyroidism, and misinterpreting lab interference from biotin supplements (which can falsely elevate free T4 and lower TSH).

Another trap is misdiagnosing central hypothyroidism as subclinical primary hypothyroidism. When both TSH and T4 are low, immediately move toward pituitary imaging, not levothyroxine therapy.

Finally, learners often forget that RAIU is contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding; in these cases, TSI testing becomes essential. Expect at least one question designed to penalize ordering RAIU when it is unsafe.

Rapid-Review Checklist

- Start with TSH → then free T4 → then determine mechanism.

- High RAIU = true hyperthyroidism; Low RAIU = thyroiditis.

- Graves = diffuse uptake; toxic nodules = focal/patchy.

- Postpartum thyroiditis = low RAIU + recent delivery.

- Central hypothyroidism = low TSH, low T4.

- Always stabilize hyperthyroid patients with beta-blockers first.

- Check cortisol before initiating levothyroxine in suspected central disease.

- Avoid RAIU in pregnancy; use TSI testing instead.

Medically reviewed by: Dr. Sarah Lang, MD, Endocrinology

References

100+ new students last month.