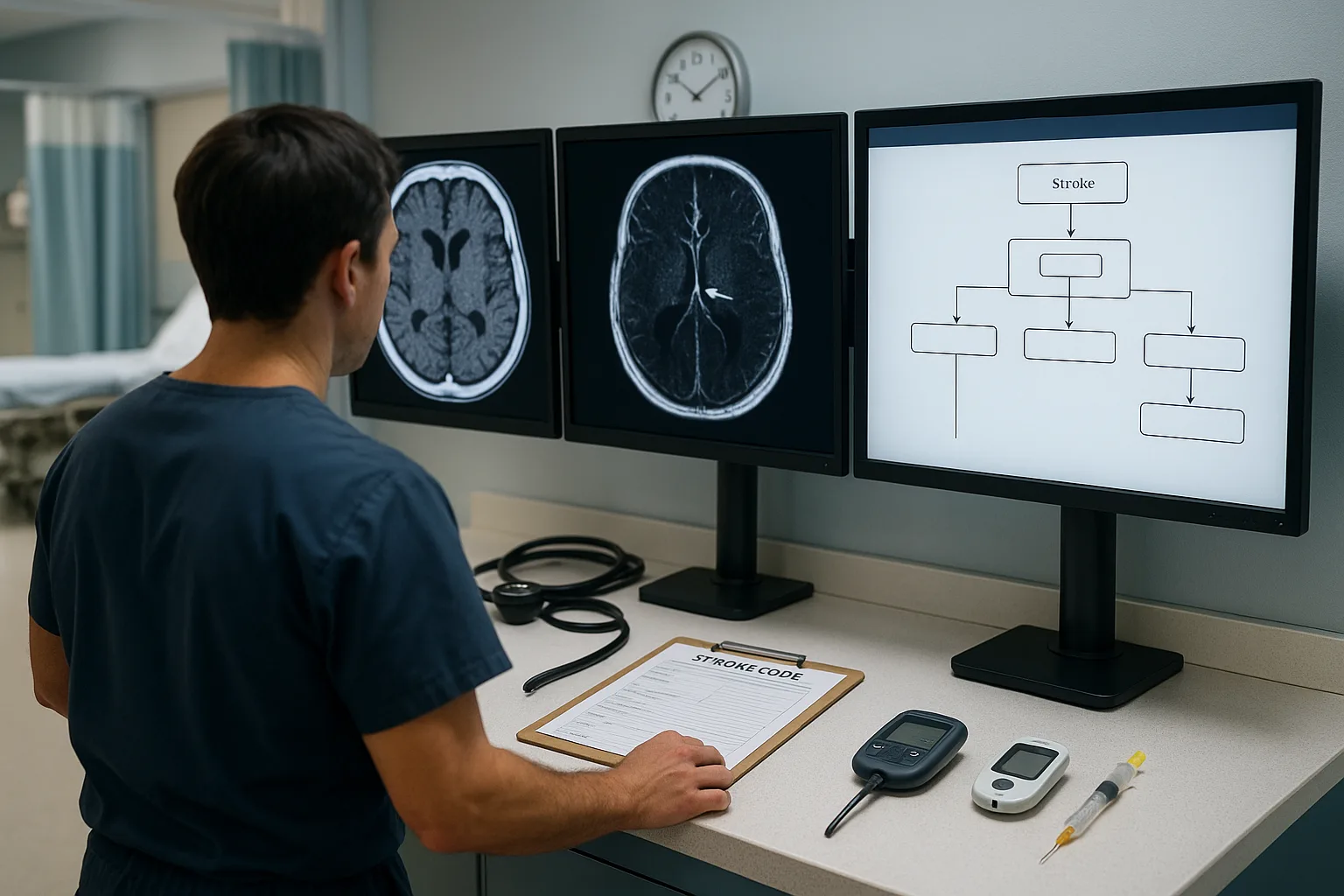

Acute ischemic stroke management on the USMLE hinges on one skill: rapidly distinguishing who receives IV thrombolytics, who qualifies for mechanical thrombectomy, and who should receive both. Because “stroke clock” logic appears repeatedly on Step 2 CK and Step 3, mastering the acute ischemic stroke algorithm is essential. Students often memorize isolated rules—tPA within 4.5 hours, thrombectomy up to 24 hours—but struggle to integrate the practical decision-making around imaging sequences, contraindications, and NIHSS thresholds. This article provides a structured, exam-ready pathway grounded in guideline-based practice, covering stabilization, non-contrast CT logic, CTA indications, and the modern thrombectomy window expansions.

The goal is to turn a classically confusing ED scenario into a reproducible flow that helps you identify which patients qualify for thrombolysis, which need endovascular therapy, and which require neither. Equally important are the distractors commonly embedded in NBME-style vignettes: mild or rapidly improving symptoms, unknown last-known-well, contraindicated anticoagulation profiles, and subtle imaging traps such as mistaking chronic microbleeds for hemorrhage.

A typical exam vignette gives you a patient with sudden focal deficits, an obvious time of onset, and a single piece of destabilizing information—blood pressure too high, glucose too low, anticoagulant status unclear, or a stroke mimic like seizure or hypoglycemia. You are expected to apply the acute ischemic stroke algorithm instantly: stabilize, correct reversible threats, order non-contrast head CT, and determine candidacy for tPA and/or thrombectomy. Unlike clinical practice, USMLE timing rules are strict. If the vignette says “symptoms began 3 hours ago,” you do not wait for MRI; if the CT has no hemorrhage, you give IV thrombolysis unless an absolute contraindication is present.

Mechanical thrombectomy is increasingly tested due to its extended therapeutic window and its dependence on large vessel occlusion (LVO) identification. The exam frequently tests your ability to detect LVO clues even before imaging—gaze deviation, dense hemiplegia, severe aphasia, or an NIHSS typically ≥6–10. Early recognition allows rapid activation of CTA or MRA imaging to confirm large-vessel blockage and expedite endovascular management. These clues are especially important in scenarios with unclear onset times where thrombectomy may still be appropriate despite tPA ineligibility.

Throughout this article, you will learn not only the criteria themselves but how to think about them in the style of the boards. Certain details—such as blood pressure thresholds prior to thrombolysis, antiplatelet use, prior strokes, and recent surgeries—are classic high-yield pitfalls. We will also address decision patterns surrounding posterior circulation strokes, which often present subtly yet qualify for similar interventions based on vessel territory and perfusion deficits.

As you move through this guide, you’ll notice frequent emphasis on pattern recognition—an essential skill for acute ischemic stroke questions. These algorithms are predictable because the exam writers want to see if you understand both the timing and safety constraints. They also want to confirm your ability to stabilize patients before definitive intervention. If airway compromise or aspiration risk appears in the vignette, secure the airway before any imaging or thrombolysis decision. If blood pressure is elevated above tPA thresholds, lower it with guideline-directed IV medications. If the patient is anticoagulated, clarify the medication and timing before giving thrombolytics. This structured approach prevents you from falling into diagnostic traps.

Where appropriate, you’ll see strategic examples referencing how the MDSteps Adaptive QBank handles stroke logic—especially questions designed to teach decision-trees through immediate feedback, automatic flashcard decks generated from missed items, and analytics that identify whether you consistently misclassify tPA vs thrombectomy cases.

In acute ischemic stroke scenarios, the first step is always stabilization. Even though stroke is primarily a neurological emergency, you must apply the same “Airway, Breathing, Circulation” structure used in trauma and critical care. Many students skip directly to scanning, but the USMLE heavily emphasizes stabilizing reversible deficits before imaging or thrombolytic decision-making.

Airway protection is a common high-yield trap. A patient with depressed mental status, inability to handle secretions, or vomiting after symptom onset should be intubated before CT imaging. Exams often present a patient with progressively worsening consciousness or aspiration risk; if you overlook airway protection, you miss the expected next step. Breathing issues—such as respiratory depression after a seizure—require oxygenation and ventilation support before neurological assessment.

Next, check fingerstick glucose immediately. Hypoglycemia is the most common stroke mimic on exams and must be corrected prior to declaring neurological deficits irreversible. If glucose is low, administer IV dextrose before ordering CT. Hyperglycemia also worsens outcomes, but the USMLE does not require tight control in the acute setting; instead, ensure values are reasonable and avoid delays in imaging.

Blood pressure management is another critical decision point. For candidates receiving IV thrombolysis, BP must be below specific thresholds (per guidelines). If too high, rapid-acting IV antihypertensives are given before tPA. However, for patients receiving only thrombectomy or no reperfusion therapy, permissive hypertension is often allowed. The exam frequently differentiates these scenarios.

Finally, ensure IV access, initiate cardiac monitoring, and obtain an ECG to identify atrial fibrillation—one of the most common causes of embolic strokes. While this does not change acute management, it reinforces the stroke’s etiology and guides long-term therapy, a topic that commonly appears in Step 2 logic questions.

The USMLE consistently tests whether you know the correct imaging order. Non-contrast CT is always first. Its purpose is singular: rule out hemorrhage. You are not evaluating for ischemia in the acute phase, because CT is often normal within the first few hours. A normal CT therefore does not rule out ischemic stroke—another classic NBME trap.

If the CT shows no bleeding, you evaluate candidacy for IV thrombolysis. If an LVO is suspected—based on severe deficits, gaze deviation, high NIHSS, or hyperdense vessel signs—you immediately proceed to vascular imaging such as CTA or MRA. The key is not to delay tPA for additional imaging unless thrombectomy eligibility is strongly suggested and thrombolysis is already contraindicated.

MRI is more sensitive but should never delay acute reperfusion decisions. Vignettes may include MRI findings after initial stabilization, but they are rarely the first diagnostic step. If time of onset is unknown, diffusion-weighted MRI can help determine salvageable tissue—but again, not at the cost of delaying necessary therapy.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

IV thrombolysis (alteplase) is primarily given within 4.5 hours of last-known-well. The USMLE focuses heavily on inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as blood pressure thresholds. Absolute contraindications include active bleeding, recent major surgery, history of intracranial hemorrhage, severe uncontrolled hypertension, and current anticoagulation with elevated INR or recent DOAC ingestion. Mild or rapidly improving symptoms do not qualify and represent another common distractor.

Mechanical thrombectomy is indicated when a large vessel occlusion is present in the anterior circulation (M1, ICA terminus) and the patient has significant deficits. Newer guidelines allow thrombectomy up to 24 hours post-onset in select patients with favorable perfusion imaging. The USMLE often tests whether you recognize LVO before imaging using bedside neurological clues.

A practical stroke algorithm must integrate stabilization, imaging, thrombolysis windows, and endovascular candidacy. Students who memorize isolated facts miss points. This section walks through a structured, reproducible decision pathway used in emergency care and reflected in Step 2 CK/Step 3 vignettes.

Stroke questions rely on distractors: misinterpreting imaging, overlooking contraindications, misunderstanding time windows, or failing to stabilize before imaging. This section outlines patterns that appear repeatedly in test questions with clinical reasoning explanations.

Try the MDSteps Adaptive QBank for stroke algorithms, live vitals, and automatic flashcards from your misses. Medically reviewed by: Jonathan Reyes, MDUnderstanding the Acute Stroke Algorithm: Time, Imaging, and Intervention

USMLE Focus

High-Yield Skill

Identify Stroke Type

Recognize sudden focal deficits, rule out mimics, check glucose immediately

Imaging Workflow

Non-contrast CT first → CTA for LVO → MRI only if needed and not delaying therapy

tPA Eligibility

Time ≤4.5 hrs, no major contraindications, BP control if needed

Thrombectomy Criteria

LVO confirmed + NIHSS elevation; window up to 24 hours in select cases

Stabilization First: Applying the ATLS Mindset to Stroke

Imaging Workflow: The Core of the Acute Ischemic Stroke Algorithm

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

100+ new students last month.

IV Thrombolysis: Precise Criteria, High-Yield Pitfalls

Mechanical Thrombectomy: Recognizing Large Vessel Occlusions

Putting It Together: The Complete USMLE Stroke Flowchart

Common NBME Traps and How to Avoid Them

Rapid-Review Checklist

References

Acute Ischemic Stroke Algorithm for the USMLE: tPA vs Mechanical Thrombectomy Simplified