Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) provides the most testable, structured clinical framework for managing an unstable trauma patient on Step 2 CK and Step 3. The exam repeatedly tests your ability to recognize priorities under pressure: stabilize first, diagnose later, and never violate ABCs. Within the first moments of a trauma vignette, the NBME evaluates whether you can distinguish between life‑saving interventions and time‑wasting diagnostics. Successful examinees think in algorithms—not guesses.

High-yield principles: airway threats always supersede imaging, hypotension in trauma is hemorrhagic until proven otherwise, and any patient who cannot protect the airway receives immediate intubation. These rules appear in dozens of trauma-themed questions.

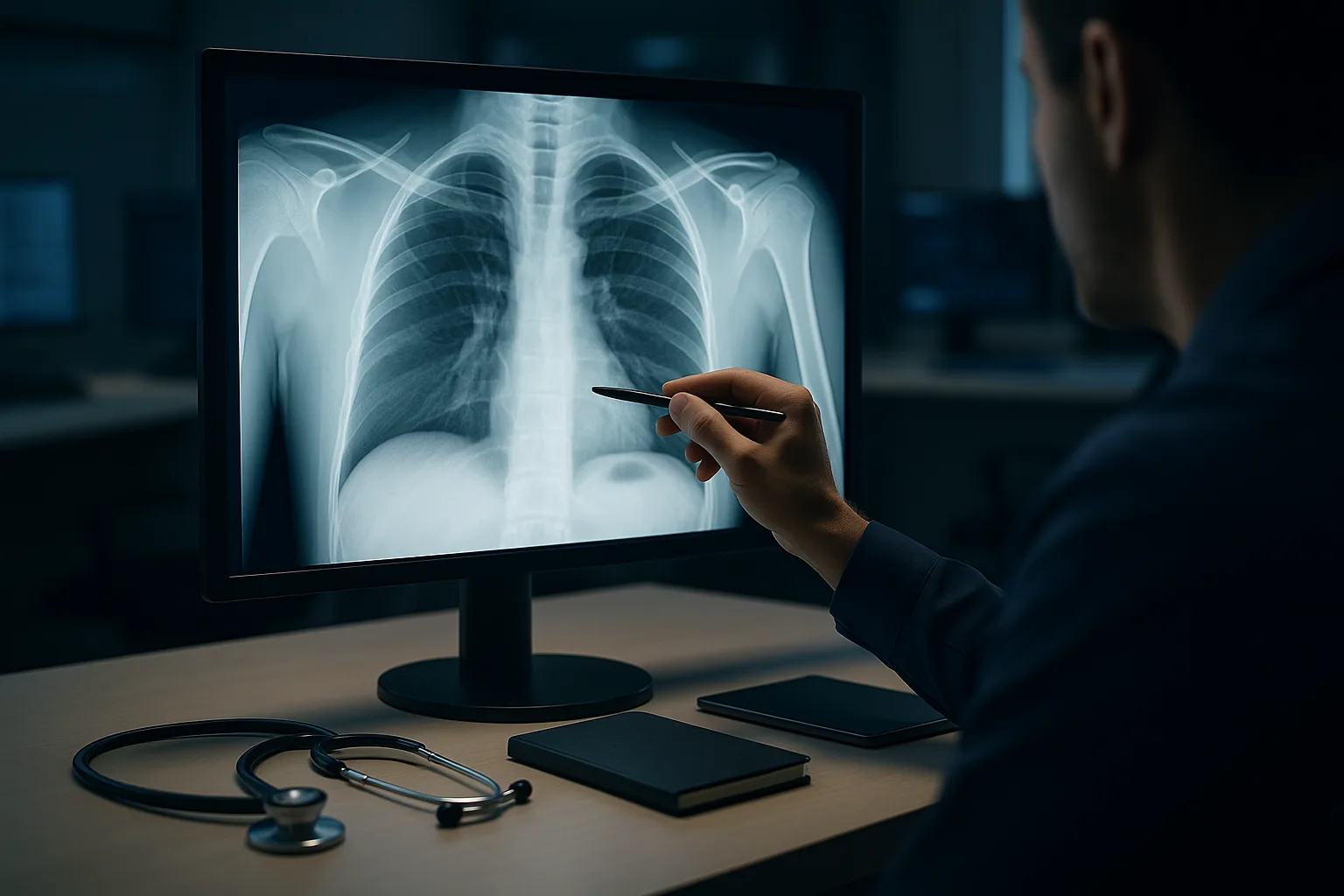

Additionally, the exams test your ability to detect unstable patterns early: tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, flail chest, massive hemothorax, pericardial tamponade, and pelvic fracture hemorrhage. Every one of these conditions demands rapid bedside interventions. While radiologic confirmation has a role, ATLS emphasizes that treatment must never be delayed to wait for diagnostics when a life-threatening process is identified clinically.

On exam day, your role is to apply ATLS thinking efficiently. MDSteps’ adaptive QBank reinforces this by surfacing trauma questions when the system detects weak patterns in airway triage, chest trauma categorization, and shock physiology. Using a question-first approach trains your brain to apply ATLS sequences automatically, which is essential for maximizing points in high‑acuity scenarios. The airway is the single most tested ATLS component. A trauma vignette often opens with a patient who is hypoxic, obtunded, or showing signs of airway compromise: hoarse voice, stridor, gurgling respirations, expanding neck hematoma, or severe facial trauma.

USMLE logic is straightforward: if the patient cannot maintain or protect the airway, you must intubate immediately. Bag‑valve‑mask ventilation is a short-term bridge, not a definitive step.

Exam traps include ordering imaging before securing the airway or performing a detailed neurologic exam before stabilizing ventilation. Another high-yield trap is hesitating to intubate a patient with impending airway loss (e.g., inhalational burns with rapidly developing edema). Early intubation is safer than waiting until the anatomy becomes distorted.

A structured checklist strengthens recall:

Tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, flail chest, and massive hemothorax are the classic chest killers tested repeatedly. Your objective is not to memorize but recognize the clinical fingerprints.

Tension pneumothorax presents with unilateral absent breath sounds, hypotension, tracheal deviation, and distended neck veins. Treatment precedes imaging: needle decompression followed by tube thoracostomy. Massive hemothorax involves >1,500 mL initial chest tube output or >200 mL/hr for several hours; these cases need thoracotomy.

Open pneumothorax requires a 3‑sided occlusive dressing followed by tube thoracostomy. Flail chest involves paradoxical chest wall motion and is managed with adequate analgesia, oxygenation, and sometimes positive pressure ventilation. Rib fractures alone are not flail; segmental fractures with independent movement are.

Compact table for exam‑day clarity:

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data. Trauma-induced shock is hemorrhagic until proven otherwise. Hypotension with tachycardia immediately triggers volume resuscitation. Step 2 CK expects you to order two large‑bore IVs and isotonic fluids, while Step 3 pushes you toward balanced transfusion strategies, especially in unstable polytrauma.

Key exam rule: permissive hypotension is appropriate in penetrating torso trauma prior to hemorrhage control but is contraindicated in traumatic brain injury.

Another common trap involves giving excessive crystalloid. Modern management favors a balanced transfusion ratio (PRBC:FFP:platelets). Pelvic fractures require binding; unstable bleeding patients need immediate surgical or interventional radiology control.

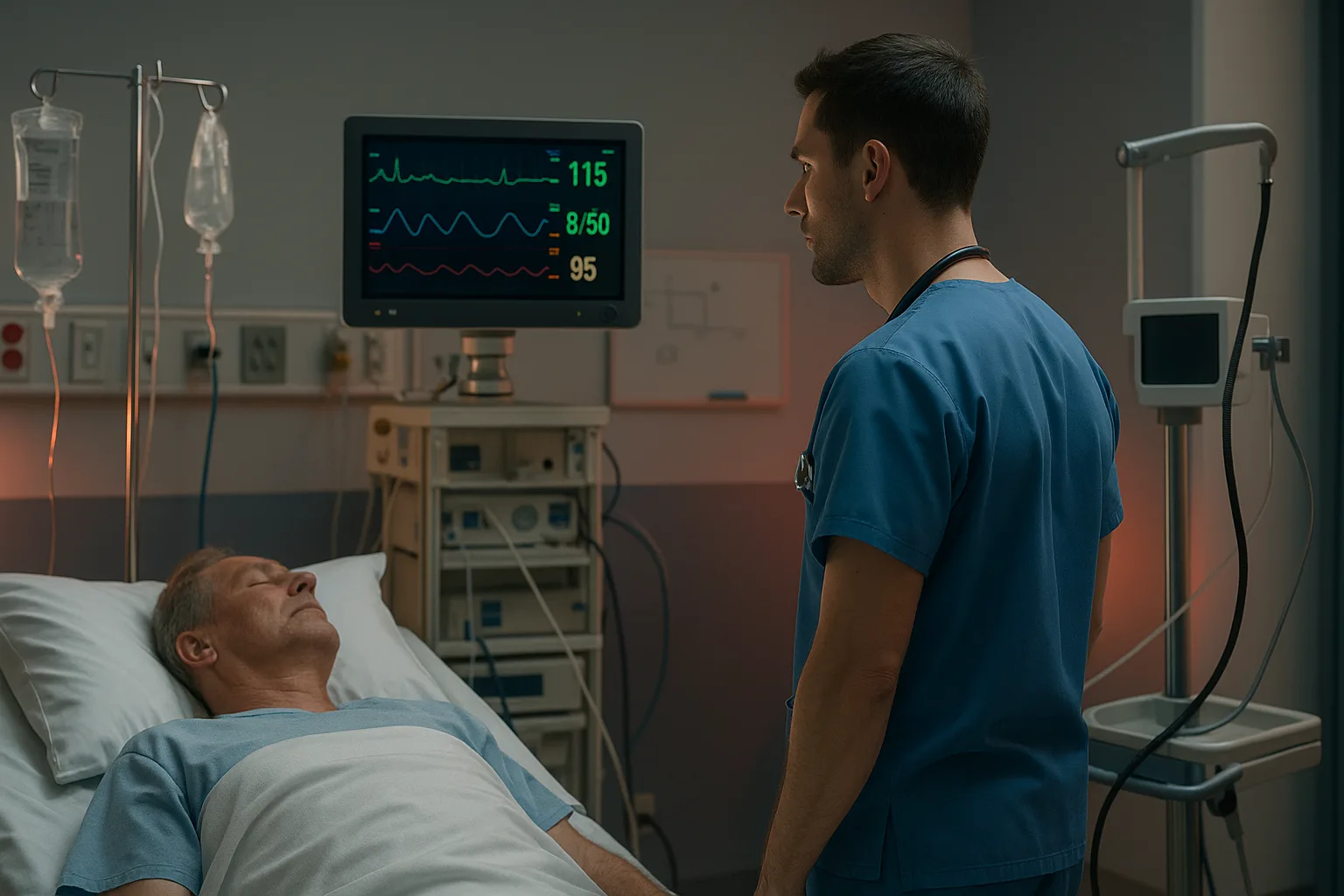

In vignettes, ultrasound (FAST exam) clarifies whether intra-abdominal hemorrhage is present. A positive FAST in an unstable patient → straight to the OR. The D of ATLS hinges on GCS scoring and identifying focal deficits rapidly. The USMLE frequently tests subtle clues: blown pupil suggesting uncal herniation, posturing patterns, or altered mentation from hypoxia versus traumatic brain injury.

If a patient is deteriorating neurologically with evidence of increased intracranial pressure, elevate the head of the bed, hyperventilate temporarily, and administer hyperosmolar therapy while arranging definitive care. Step 3 emphasizes nuance: hyperventilation is a bridge, not maintenance therapy. Exposure means complete disrobing while preventing hypothermia. After the primary survey, imaging decisions depend entirely on stability. Stable trauma patients go to CT; unstable patients go to the OR.

Step 2 CK focuses on recognizing when imaging is inappropriate—for example, ordering CT chest in a patient needing immediate thoracostomy. Step 3 pushes your ability to handle serial assessments: continued hypotension despite intervention means missed bleeding.

Secondary survey includes head‑to‑toe inspection, pain assessment, and re‑evaluation of vitals. NBME loves to place the critical finding—pelvic instability, perineal bruising, tracheal deviation—inside the secondary survey narrative. Several patterns recur across exams:

Medically reviewed by: John R. Patel, MD, Emergency MedicineATLS Logic: The Framework Behind Trauma Decision‑Making

Airway: The Most Tested Step in Trauma

Step 3 emphasizes decision‑making under uncertainty. If multiple priorities compete—such as airway compromise and external hemorrhage—you choose the threat that kills first: airway. MDSteps’ real‑time analytics dashboard is particularly useful here because it identifies handling errors in airway triage and generates flashcards automatically from missed questions.Breathing & Ventilation: Rapid Identification of Chest Killers

Condition Key Clues Immediate Step Tension pneumothorax Hypotension + absent breath sounds + deviation Needle decompression Open pneumothorax “Sucking” chest wound 3‑sided dressing Flail chest Paradoxical movement Positive pressure ventilation Massive hemothorax >1500 mL chest tube return Thoracotomy Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

100+ new students last month.

Circulation & Hemorrhagic Shock

Neurologic Assessment: Disability and GCS

Exposure, Imaging, and Secondary Survey

High‑Yield Trauma Patterns You Must Master

Students often lose points not from lack of knowledge but from improper sequencing. Practicing trauma vignettes in MDSteps’ Adaptive QBank reinforces the correct order through repetition and targeted analytics.Rapid-Review Checklist

Citations

Mastering Trauma Resuscitation on Step 2 CK & Step 3: How to Apply ATLS Logic Under Pressure