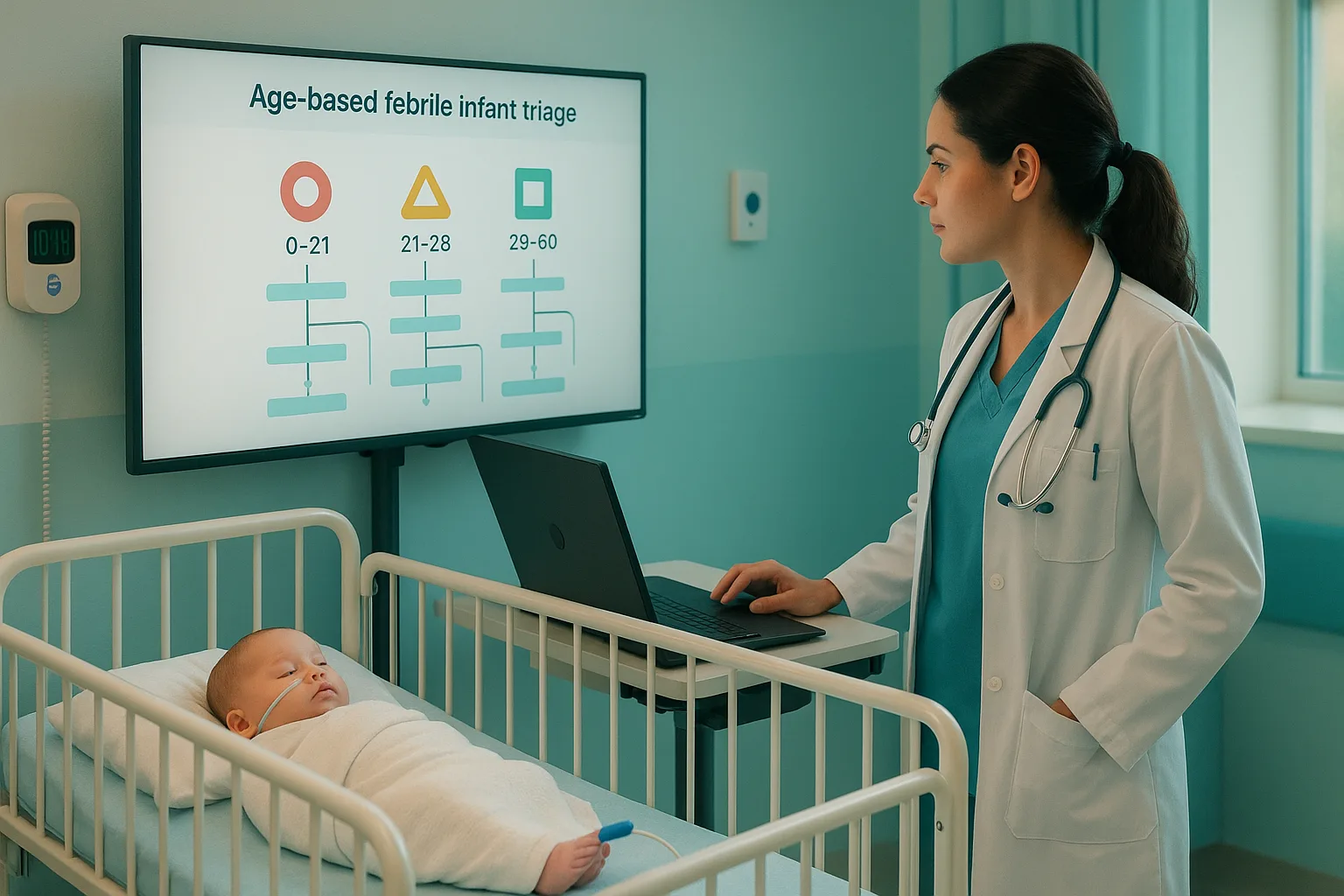

A rectal temperature of ≥38.0°C (100.4°F) in an infant under 3 months looks innocent on paper, but on the exam it is a high-stakes scenario. Behind the question stem, the test writer is asking whether you can safely apply the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) febrile infant algorithm: who is a true emergency, who can be risk-stratified, and who can go home with close follow-up. The entire game is deciding which babies are low-risk versus high-risk for invasive bacterial infection (IBI) and urinary tract infection (UTI). For USMLE purposes, a “febrile infant” in this context is: Your job on Step 2 CK and Step 3 is not to memorize every possible cutoff, but to recognize the age-based pattern: the younger the infant, the more the algorithm assumes high risk. The AAP febrile infant algorithm operationalizes this by combining three pillars: On exams, the vignette almost always hands you enough information to put the child into one of three buckets: Many students overthink these questions, trying to recall every detail. Instead, follow an exam-oriented, algorithmic approach: The AAP febrile infant algorithm is explicitly testable because it sits at the intersection of pediatrics, ID, and emergency medicine. Step 2 CK will emphasize practical decision-making; Step 3 may layer on timing of cultures, route of antibiotics, and disposition. Step 1 is less focused on algorithmic management, but basic science questions can still reference why neonates have higher risk of IBI (immature immunity, poor localization of infection). In the rest of this article, we’ll walk through the age groups from youngest to oldest, highlighting exactly when to treat a febrile infant as high-risk, when they can be considered low-risk, and how that translates into the “next best step” answer choices you’ll see on boards. The AAP febrile infant algorithm focuses on well-appearing term infants 8–60 days old, but exam questions often extend the discussion to 0–90 days. The key principle is that management intensity declines with increasing age, provided the infant looks well and inflammatory markers are low-risk. Before you start memorizing lab cutoffs, internalize this sequence: You do not need exact numeric cutoffs for USMLE, but you should recognize patterns consistent with high-risk inflammation: A classic exam trap is a 5-week-old (35 days) who is well-appearing but has an elevated ANC and positive UA. Students sometimes underreact, choosing “no further testing”. The algorithm says this infant is not low-risk: they have objective evidence of bacterial infection and may need LP, IV antibiotics, and at least brief observation in the hospital. When you practice with a high-quality QBank, pay attention to how different vignettes encode these details. A platform like MDSteps, with an adaptive QBank of over 9000 questions and analytics that highlight patterns in your misses, can help you recognize age- and lab-based cues that separate low-risk from high-risk infants long before test day. For infants under about 3 weeks, the AAP and most institutional pathways treat fever as an emergency. Their immune systems are immature, barriers to infection are thin, and they are poor at localizing infection. On exams, the best answer is almost always a full sepsis workup plus admission and empiric IV antibiotics, regardless of how “well” the infant looks. The exam logic is straightforward: you do not send these babies home. Even a completely well-appearing 10-day-old with a documented rectal temperature of 38.3°C gets blood, urine, CSF, antibiotics, and admission. If you see a neonate and your brain hesitates between “full workup and admit” versus “outpatient observation,” pick the aggressive option. On USMLE questions, do not be distracted by reassuring details like “continued to breastfeed” or “mild nasal congestion.” If the infant is under 21 days with fever, the default is that they are at high risk for IBI and must be treated as such. Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data. By 3–4 weeks, the risk profile improves slightly, but these infants remain a vulnerable group. The AAP guideline allows more nuance here, but Step 2 CK still expects a conservative approach. Think of 22–28 days as a zone where you must obtain objective data before even considering less aggressive management. On the exam, you are unlikely to be asked to send home a 24-day-old with fever, even if labs look okay. The safer answer is usually some combination of LP, IV antibiotics, and admission for observation. The nuance is that these infants are no longer automatic full sepsis workup cases; there is at least a conceptual pathway to less invasive management when all inflammatory markers and UA are normal. Expect stems like: In the first case, borderline labs may still prompt LP and admission on exam. In the second, a clearly positive UA means you cannot ignore a UTI. Even if the infant remains well-appearing, empiric parenteral antibiotics and close observation are expected. The 29–60 day group is where the AAP febrile infant algorithm really shines and where Step 2 CK questions become most nuanced. These infants are old enough that the base rate of IBI is lower, but still high enough that you cannot be cavalier. The algorithm here hinges on inflammatory markers and urinalysis. A well-appearing 5–8 week-old febrile infant is generally considered lower risk if: In that context, management can reasonably avoid LP, IV antibiotics, and admission, instead focusing on oral hydration, parental education, and close follow-up within 24 hours. But any abnormality pushes the infant toward higher-risk management. In these situations, exam answers typically include LP, parenteral antibiotics, and either admission or very close observation with clear return precautions if discharged. Consider a 45-day-old infant with rectal temperature 38.6°C, well-appearing, ANC significantly elevated, CRP mildly elevated, and a negative UA. This infant does not meet low-risk criteria. The most appropriate management usually includes a lumbar puncture, blood and urine cultures, empiric IV antibiotics, and admission or very close observation. By contrast, a 55-day-old infant with fever 38.1°C, completely normal UA and inflammatory markers, and reliable parents might be managed without LP or admission, focusing on close outpatient follow-up. On the exam, the “next best step” would be something like “discharge home with prompt follow-up within 24 hours and strict return precautions,” not “start broad-spectrum IV antibiotics.” This is where repetitive, analytics-driven practice helps. If you repeatedly miss questions about febrile infants, a system like the MDSteps automatic study plan and flashcard generator (which can export to Anki) can pull all your misses related to pediatric emergencies, including the febrile infant algorithm, and turn them into a targeted micro-curriculum. Once infants cross the 60-day mark, the risk profile improves further. Many institutional pathways covering 0–90 days treat 61–90-day-old infants more like older children, emphasizing careful evaluation for UTI and the overall clinical picture rather than automatic sepsis workups. For exams, this is the group where outpatient management is most clearly acceptable when the infant is well-appearing and labs are reassuring. On Step 2 CK, a well-appearing 70-day-old with fever and a clear viral URI, normal UA, and reassuring vitals can be managed as an outpatient with supportive care and close follow-up. However, if UA is positive, the infant will need antibiotics for UTI, often oral unless they appear ill or have poor oral intake. Remember that USMLE writers love to tweak small details: a subtle change in age, UA, or appearance can flip the correct answer from “send home with close follow-up” to “admit for sepsis workup.” Always re-check age and vital signs before you pick your answer. Beyond memorizing the AAP febrile infant algorithm, you need a pattern library of vignettes in your head. Examiners frequently recycle the same scenarios with minor twists, counting on you to over- or under-react. To solidify these patterns, mix reading and retrieval practice. After reviewing an algorithm, challenge yourself with board-style stems and force a timed decision before looking at the explanation. Over time, you should be able to intuit the correct age-based pathway within a few seconds of reading the first line of the question. Use this section as a final pass just before your pediatric shelf or Step 2 CK. If you can run this checklist in your head under time pressure, you are functionally applying the AAP febrile infant algorithm on exam day. Integrating this algorithm into your day-to-day studying is easier if you repeatedly see it in action. An adaptive QBank with robust analytics and an exam readiness dashboard can show you whether you are truly consistent with febrile infant questions, rather than relying on gut feeling. As you approach test day, make sure these scenarios feel routine, not exotic.

Medically reviewed by: Jordan Lee, MD, FAAP

Why Febrile Infants ≤90 Days Are a Different Beast on Step 2 CK

Core Logic of the AAP Febrile Infant Algorithm: Age, Appearance, and Inflammation

Stepwise mental model for the algorithm

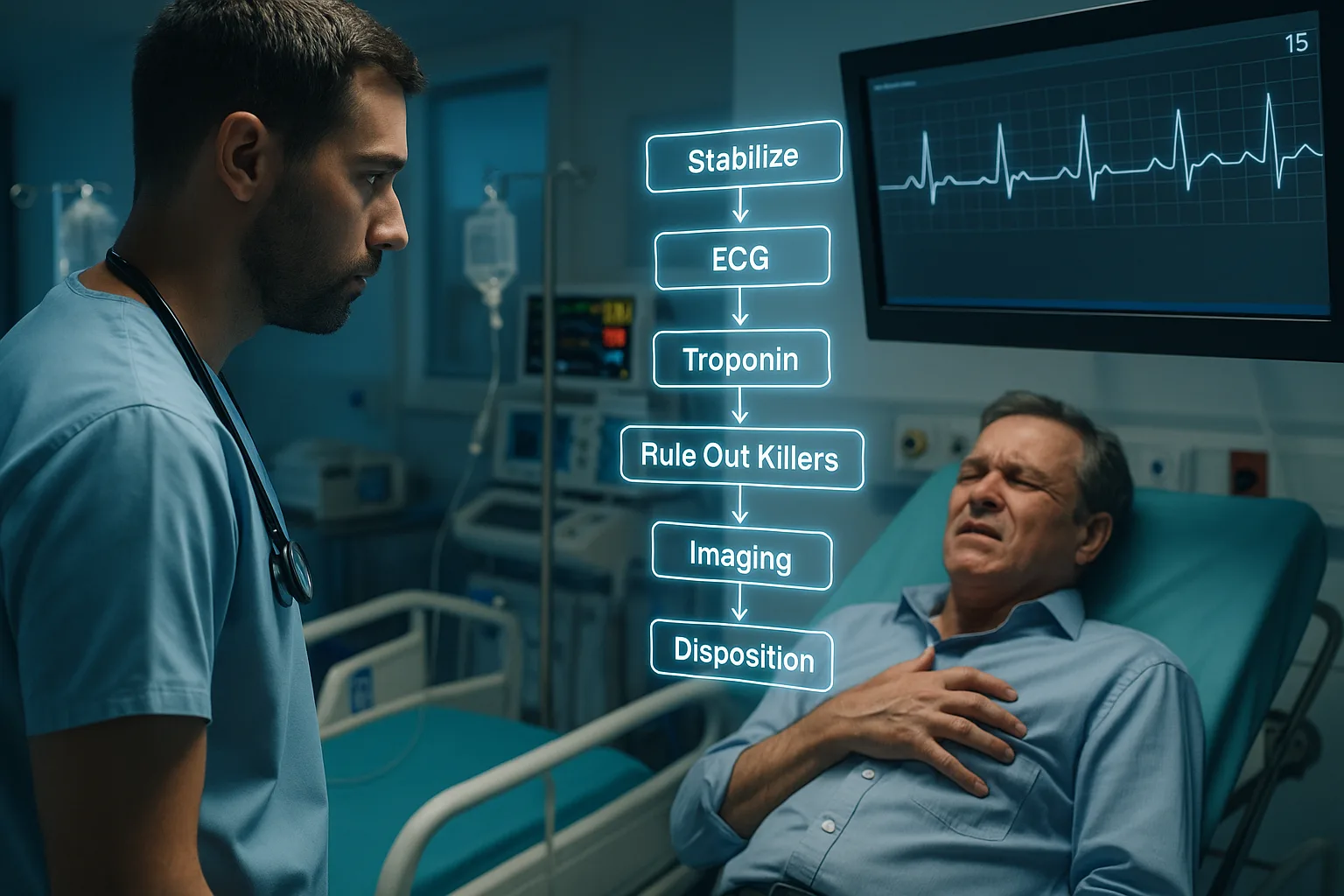

Any signs of toxicity (lethargy, poor perfusion, hypotension, respiratory distress, bulging fontanelle, or shock) override everything. Immediate sepsis workup, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, and PICU-level care may be required. These are always high-risk.

The AAP guideline uses combinations of temperature, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin to define “abnormal” inflammation. In general, elevated markers push you toward LP, IV antibiotics, and admission; normal markers plus reassuring UA pull you toward outpatient management in older infants.

UTI is the most common serious bacterial infection in this age group. A positive UA alone can convert an otherwise low-risk infant into a child requiring antibiotics, even if they might still avoid LP and admission depending on age and other labs. High-yield inflammatory marker patterns

0–21 Days: Everyone Is High-Risk Until Proven Otherwise

Algorithm for 0–21 days

Simplified 0–21 day algorithm (mental flowchart)

Classic vignette red flags (always high-risk)

Common Step 2 CK traps

In this age group, this is wrong. The threshold for LP and admission is extremely low.

If the infant is unstable, start antibiotics immediately after cultures are drawn; do not delay life-saving therapy for perfect data.

Once the infant has been discharged home and then presents with fever, the AAP febrile infant algorithm is appropriate, but the first 3 weeks are still managed as very high risk. Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

100+ new students last month.

22–28 Days: Still High-Risk, but Labs Start to Matter

Key questions for 22–28 days

If ill-appearing, treat just like <21 days: full sepsis evaluation, IV antibiotics, admission.

Abnormal UA, high ANC, elevated CRP or procalcitonin, or very high temperature all push the infant into high-risk territory.

CSF with pleocytosis or uninterpretable (e.g., traumatic tap) is managed as high-risk meningitis until proven otherwise.

Scenario (22–28 days, well-appearing) Risk Category Typical Management Abnormal inflammatory markers and/or positive UA High risk for IBI or UTI LP, IV antibiotics, hospital observation Normal markers, negative UA, reassuring CSF Lower risk (selected cases) Often still admitted; some pathways allow close home observation LP not done or uninterpretable, but labs concerning High risk by default Admit, IV antibiotics, repeat evaluation USMLE-style vignette framing

29–60 Days: True Low-Risk vs High-Risk Stratification

Defining low-risk in 29–60 days (exam perspective)

High-risk features in 29–60 days

Translating the algorithm into USMLE answer choices

61–90 Days: Focus on UTI and Outpatient Management

Principles for 61–90 days

Sample exam contrasts

→ Outpatient observation with clear return precautions and follow-up is appropriate.

→ Diagnose UTI, start appropriate antibiotics (often oral), and consider short observation or admission only if there are risk factors such as vomiting, poor intake, or unreliable follow-up.

→ Treat as ill-appearing; obtain blood, urine, possibly CSF, start parenteral antibiotics, and admit. Building a Mental Library of Vignettes and Avoiding Classic Exam Traps

High-yield vignette patterns

Common Step 2 CK and Step 3 traps

Below 21–28 days, appearance does not rescue the infant from a full workup and admission. The most conservative option is usually correct.

A positive RSV or influenza test does not exclude bacterial co-infection. Do not ignore abnormal UA or inflammatory markers just because a virus is present.

For 29–90 days, not checking a UA or ignoring a positive UA is a common distractor. UTI remains the leading serious bacterial infection in this age range.

If an infant is ill-appearing or hypotensive, you prioritize resuscitation and empiric antibiotics after cultures; you do not delay treatment for perfect data. Rapid-Review Checklist for Febrile Infants (≤90 Days) + References

Rapid-Review Checklist

Exam-Day Essentials

References and Further Reading

Low-Risk vs High-Risk Febrile Infants: Applying the AAP Guidelines on Step 2 CK (AAP Febrile Infant Algorithm)