Learn a practical, exam-focused algorithm for evaluating low sodium, recognizing dangerous presentations, and choosing the right therapy for different hyponatremia patterns on the boards.

Why Hyponatremia Matters on the Boards (and How to Think Algorithmically)

Hyponatremia shows up everywhere on USMLE exams: ICU vignettes with seizures, oncology cases with small cell lung cancer, heart failure admissions with fluid overload, and psychiatry stems with psychogenic polydipsia. If you rely on memorized lists of causes instead of an organized hyponatremia diagnostic and treatment algorithm, these questions quickly become guesswork. This article walks through a structured approach that mirrors how test writers construct cases—and how clinicians safely manage sodium disorders in real life.

Start by reframing low sodium as a problem of water balance, not just “electrolytes.” On exams, sodium concentration changes almost always reflect relative excess or deficit of free water compared with solute. The key questions are: Is the lab value real? Is the plasma truly dilute? What is the patient’s effective volume status? How fast did this develop, how severe are the symptoms, and how aggressively can you correct it without causing osmotic demyelination?

USMLE stems usually embed those questions in their wording. Look for clues:

- Time course: “Sudden onset confusion after marathon” suggests acute; “months of fatigue” suggests chronic.

- Brain symptoms: Headache, vomiting, seizures, coma point to severe, symptomatic disease.

- Volume status: Orthostasis and dry mucous membranes versus JVD, edema, and crackles.

- Context: Thiazide use, SIADH-inducing meds, endocrine disorders, or polydipsia behaviors.

The boards rarely ask you for a random lab value; they want to know if you can choose the next best step aligned with a tested algorithm. A classic trap is jumping straight to hypertonic saline or fluid restriction without first verifying the type of hyponatremia and the patient’s hemodynamic stability. Another common mistake is ignoring the distinction between acute and chronic disease, leading to overly rapid correction in a stable, chronically low sodium patient.

Throughout this guide, we will break hyponatremia into logical branches: confirming a true low sodium, classifying by osmolality, stratifying by volume status, and then tailoring treatment based on symptoms and chronicity. This is exactly how a good question bank trains you—ideally with multiple vignettes that force you to apply the same framework across different specialties. When you practice on platforms like the MDSteps Adaptive QBank, aim to mentally run this algorithm every time a sodium value appears, even if it is not the “headline” abnormality in the stem.

By the end of this article, you should be able to read a hyponatremia vignette and immediately map it to a decision tree: stabilize first if necessary, confirm the lab, classify the disorder, and adjust sodium in a safe, controlled way. The more you practice this pattern, the more these questions become automatic points rather than anxiety triggers.

Step 1: Confirm a True Low Sodium and Rule Out Pseudohyponatremia

The first step in any hyponatremia algorithm is simple but high-yield: confirm that the low sodium represents a real hypotonic state. USMLE stems love to present patients with a sodium in the 120s and then test whether you recognize when that number is misleading. If you reflexively treat every low sodium with fluid restriction or saline, you will fall into classic traps.

Start with the following basic checks:

- Repeat the test if the story suggests lab error (e.g., asymptomatic outpatient with no risk factors and a previously normal value).

- Check serum glucose and calculate a corrected sodium in marked hyperglycemia.

- Review serum osmolality to differentiate hypotonic from isotonic or hypertonic states.

In hyperglycemia, water shifts from the intracellular to the extracellular space, diluting sodium. The exam expects you to know the approximate correction:

- Corrected Na ≈ measured Na + 1.6 mEq/L for every 100 mg/dL glucose above 100.

If the corrected sodium is near-normal, the problem is primarily hyperosmolar hyperglycemia, not a true sodium disorder. Management focuses on insulin and volume resuscitation, not hypertonic saline or fluid restriction.

Next, consider pseudohyponatremia, which appears as low sodium but with a normal serum osmolality. This scenario arises in severe hyperlipidemia or marked hyperproteinemia, where the lab’s measurement method underestimates sodium concentration in the aqueous phase of plasma. On exams, this shows up in patients with:

- Multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy

- Very high triglyceride levels (for example, pancreatitis risk)

Key board clue: sodium is low, but measured serum osmolality is normal, and the patient has no symptoms of cerebral edema. The management is to treat the underlying lipid or protein disorder, not to give saline or restrict fluids. Recognizing this distinction earns you easy points and prevents iatrogenic harm in real life.

Finally, some patients have hypertonic hyponatremia, classically due to high glucose or exogenous osmoles like mannitol. Here, serum osmolality is elevated, sodium is low, and the brain is actually exposed to a hyperosmolar environment. Treat the underlying hyperosmolar state; there is no indication for hypertonic saline just to “fix” the sodium number.

Consolidate this step in your mind:

| Pattern | Serum Osmolality | Typical Cause | USMLE Key Move |

| True hypotonic hyponatremia | Low | SIADH, volume depletion, CHF, cirrhosis, etc. | Proceed to volume status and urine studies |

| Pseudohyponatremia | Normal | Hyperlipidemia, hyperproteinemia | Treat underlying disorder; no sodium therapy |

| Hypertonic hyponatremia | High | Hyperglycemia, mannitol, contrast | Correct the hyperosmolar state |

Whenever you see low sodium on a vignette, ask first: “Is this truly hypotonic?” That question prevents premature treatments and aligns your approach with high-yield exam logic.

Step 2: Classify Hypotonic Hyponatremia by Volume Status

Once you have confirmed a true hypotonic state, the next key branch in the algorithm is the patient’s effective volume status. Exams relentlessly test your ability to distinguish hypovolemic, euvolemic, and hypervolemic hyponatremia based on physical findings, history, and sometimes subtle lab patterns.

Begin with the clinical exam:

- Hypovolemic: Dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, possible prerenal azotemia.

- Euvolemic: No overt edema or signs of volume depletion; normal vitals or mild changes.

- Hypervolemic: Edema, ascites, elevated JVD, pulmonary crackles; often heart failure, cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome.

Laboratory data help refine this classification. The exam often includes urine sodium and urine osmolality as decision points. For hypovolemic states, further divide by renal vs extrarenal losses:

- Renal losses: Diuretics, mineralocorticoid deficiency, salt-wasting nephropathies. Expect urine sodium > 20–30 mEq/L.

- Extrarenal losses: Vomiting, diarrhea, third spacing, burns. Kidneys avidly retain sodium; urine sodium < 20 mEq/L is typical.

In euvolemic hypotonic hyponatremia, the big three exam diagnoses are:

- SIADH: Inappropriately concentrated urine (high urine osmolality and sodium), low serum uric acid, normal thyroid and adrenal function.

- Primary polydipsia or low solute intake: Very dilute urine with low urine osmolality due to overwhelming water intake or insufficient osmoles (“beer potomania,” “tea and toast”).

- Endocrine causes: Adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism, which mimic SIADH unless specifically ruled out.

Hypervolemic hypotonic hyponatremia arises when total body sodium is increased but total body water is increased even more. Effective arterial blood volume is low, triggering neurohormonal responses:

- Congestive heart failure

- Cirrhosis with portal hypertension

- Nephrotic syndrome and advanced kidney disease

These patients often have edema or ascites and elevated JVP. Urine sodium is usually low (because the kidneys retain sodium in response to perceived hypoperfusion), unless they are on diuretics or have intrinsic renal dysfunction.

To keep this straight during questions, visualize a simple matrix:

| Volume Status | Common Causes | Physical Exam | Typical Urine Na |

| Hypovolemic | GI loss, diuretics, adrenal insufficiency | Dry mucosa, orthostasis, tachycardia | Low (< 20) in extrarenal loss; high in renal loss |

| Euvolemic | SIADH, hypothyroid, adrenal insuff., polydipsia | No edema, no orthostasis, often subtle | Often > 20 in SIADH; very low osmolality in polydipsia |

| Hypervolemic | CHF, cirrhosis, nephrotic, renal failure | Edema, JVD, ascites, crackles | Usually low (< 20), unless on diuretics or renal failure |

When a vignette gives you sodium, serum osmolality, urine sodium, and urine osmolality, pause and run through this classification before jumping to treatment. This habit aligns your thinking with exam writers and helps you avoid confusing similar presentations like SIADH versus hypovolemic states.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

Step 3: Identify Symptoms, Time Course, and Risk of Brain Herniation

Not all low sodium levels are equally dangerous. A patient with a sodium of 118 mEq/L who is walking and talking is a completely different scenario from a patient at 125 mEq/L having tonic-clonic seizures. USMLE questions hinge on your ability to integrate severity of symptoms and acuity of onset into the algorithm, not just memorize threshold numbers.

Think of three broad symptom categories:

- Mild: Nausea, headache, mild forgetfulness, subtle gait changes.

- Moderate: Vomiting, confusion, lethargy, more pronounced gait disturbance.

- Severe: Seizures, coma, respiratory arrest, signs of increased intracranial pressure.

Acuity matters because the brain adapts to chronic hyponatremia by losing osmoles and water to reduce swelling. When the fall in sodium is rapid (approximately < 48 hours), there is less time for adaptation, and the risk of herniation is higher at any given sodium value. In contrast, chronic hyponatremia is less likely to cause dramatic cerebral edema but becomes vulnerable to damage if corrected too quickly.

This leads to two different dangers:

- Acute severe hyponatremia: Immediate risk of brain herniation; treat quickly with hypertonic saline when seizures or impending herniation are present.

- Chronic hyponatremia: Risk of osmotic demyelination if correction exceeds recommended daily limits, especially in patients with alcoholism, malnutrition, or liver disease.

On exams, you often have to choose between “hypertonic saline bolus,” “normal saline infusion,” “fluid restriction,” “desmopressin,” or “no acute therapy.” The right choice depends on both symptom severity and chronicity, even if the stem does not explicitly state “acute” or “chronic.” Look for phrases like:

- “Developed over the past few hours” versus “for several months.”

- Recent use of hypotonic fluids or postoperative free water intake.

- End-stage liver disease with long-standing low sodium on prior labs.

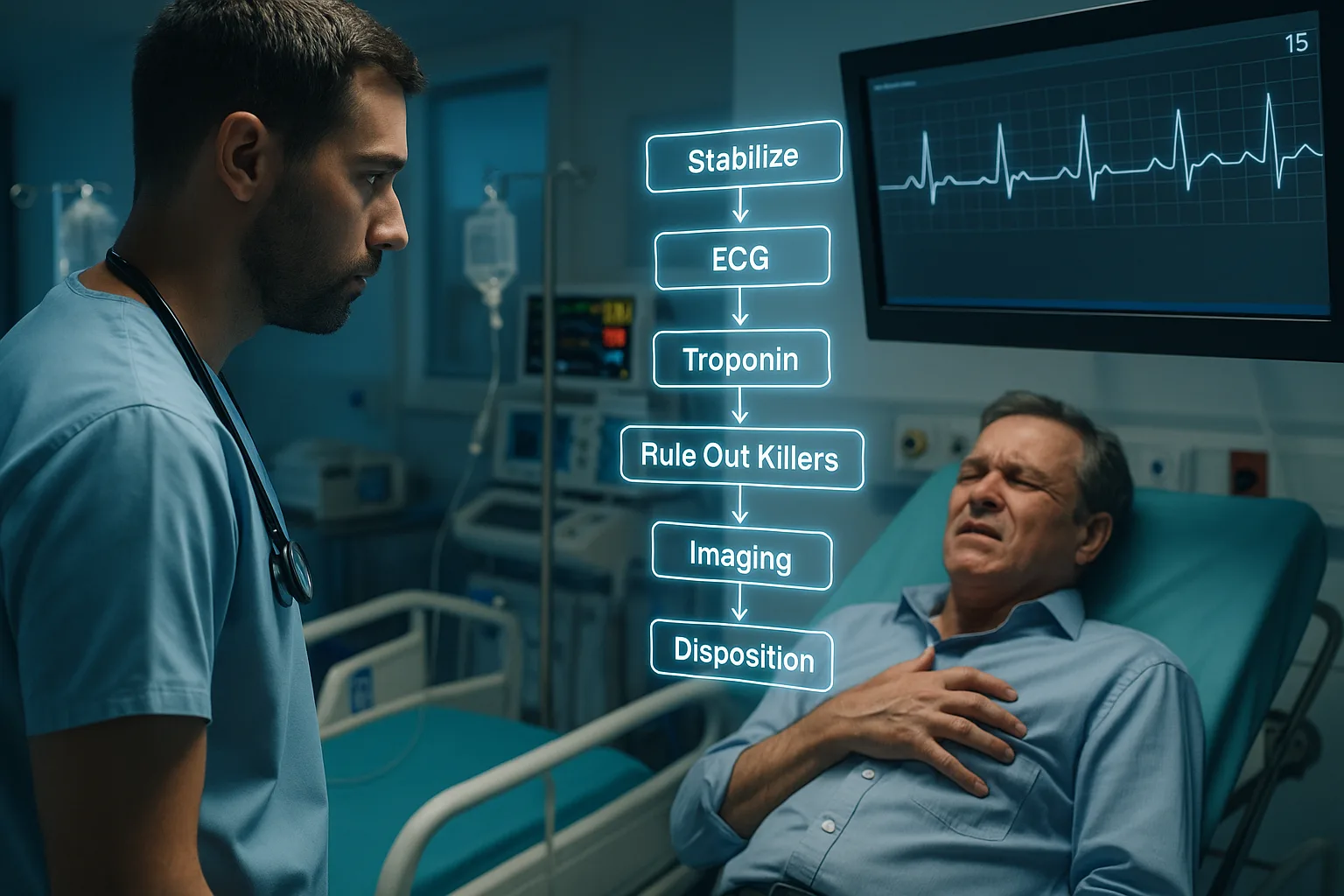

To keep your exam approach straight, mentally sketch a branching flowchart:

Symptom-Based Hyponatremia Triage (Conceptual Flow)

- Assess airway, breathing, circulation; stabilize first.

- Check for seizures, coma, signs of herniation (severe symptoms).

- If severe symptoms → consider immediate hypertonic saline bolus.

- If mild or moderate symptoms → classify as acute vs chronic; plan slower correction.

- Always pair treatment choice with volume status and etiology.

Practicing with realistic board-style questions is crucial. For example, the MDSteps Adaptive QBank can present you with back-to-back hyponatremia vignettes that look similar at first glance but diverge based on symptom severity or chronicity. The repetition forces you to ask, “Is this patient unstable?” before picking an answer, mirroring the way you should think on test day and in clinical care.

Step 4: Treatment Principles and Safe Correction Limits

Once you know the type of hyponatremia and the clinical severity, the next step is choosing therapy that corrects sodium at a safe rate. The boards consistently test not only what treatment to use, but also how aggressively to use it. Overcorrection risks osmotic demyelination, particularly in patients with chronic hyponatremia, alcoholism, liver disease, or malnutrition.

A practical rule for the exam is to aim for a rise in serum sodium of no more than 8–10 mEq/L in 24 hours, with even stricter limits (for example, ≤ 6 mEq/L per day) in high-risk patients. The goal is often to relieve acute cerebral edema symptoms rather than normalize sodium immediately.

Broad treatment strategies by scenario:

- Severe symptomatic hypotonic hyponatremia (seizures, coma):

Immediate hypertonic saline is indicated. Guideline-based approaches often use small boluses of 3% saline (for example, 100 mL over 10 minutes) repeated as needed while monitoring sodium. On exams, look for hypertonic saline when there are seizures and clear evidence of acute onset. - Hypovolemic hypotonic hyponatremia without severe symptoms:

Treat with isotonic normal saline to restore effective circulating volume. As volume is corrected, ADH levels fall and sodium rises. This can occasionally overshoot, so monitor sodium and consider slowing correction if it rises too quickly. - Euvolemic hypotonic hyponatremia (e.g., SIADH):

First-line therapy on exam is usually fluid restriction. Depending on the scenario, you may see salt tablets, loop diuretics, or vasopressin receptor antagonists in more advanced questions. Always rule out adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism, which need hormonal replacement. - Hypervolemic hypotonic hyponatremia (CHF, cirrhosis, nephrotic):

Combine fluid restriction with sodium restriction and loop diuretics. In heart failure, optimize guideline-directed medical therapy; in cirrhosis, consider measures to manage portal hypertension and ascites.

A unique board scenario is overcorrection. For instance, a patient with chronic SIADH who is treated with aggressive saline and diuretics may have their sodium jump more than 10–12 mEq/L in less than 24 hours. The correct next step is often to re-lower sodium using hypotonic fluids and/or desmopressin to reduce the risk of osmotic demyelination. Recognizing this scenario is a classic high-yield question.

To organize these concepts, you can imagine a simple schedule-style matrix that pairs clinical severity with correction goals:

| Scenario | Initial Goal | Therapy | Daily Correction Target |

| Acute severe symptomatic | Rapidly relieve cerebral edema | 3% saline bolus | Up to 4–6 mEq/L rapidly, then slow |

| Chronic, high-risk (e.g., cirrhosis) | Gradual improvement | Tailored fluids, often restriction | ≤ 6 mEq/L per 24 hours |

| Stable hypovolemic | Restore volume | Normal saline | Usually < 8–10 mEq/L per 24 hours |

As you review question explanations, pay attention not just to the choice of fluid but also to the rationale behind the rate of correction. That reasoning is what the exam is really testing.

Step 5: Applying the Algorithm to Classic USMLE Vignettes

To truly master hyponatremia for the boards, you need to apply the algorithm repeatedly to realistic vignettes. Let’s walk through a few archetypal patterns and highlight the exam logic in each.

Case 1: Postoperative seizure

A 45-year-old woman, 12 hours after major surgery, develops a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. She has been receiving hypotonic IV fluids and is afebrile. Labs show sodium of 118 mEq/L, low serum osmolality, and normal glucose. Volume status is euvolemic, and there is no history of liver disease or alcoholism.

- Step 1: True hypotonic hyponatremia? Yes (low sodium and low serum osmolality).

- Step 2: Volume status? Euvolemic.

- Step 3: Severity and acuity? Acute onset with seizure = severe symptomatic.

- Step 4: Treatment? Immediate hypertonic saline bolus to decrease cerebral edema.

The best answer is hypertonic saline, not normal saline or fluid restriction. The exam rewards recognizing acute severe neurologic symptoms as a separate pathway in the algorithm.

Case 2: Thiazide-induced hypovolemia

A 70-year-old man on hydrochlorothiazide presents with dizziness, dry mucous membranes, and orthostatic hypotension. Sodium is 126 mEq/L, serum osmolality is low, urine sodium is high, and BUN/creatinine suggests prerenal azotemia.

- True hypotonic hyponatremia? Yes.

- Volume status? Hypovolemic.

- Likely cause? Renal sodium loss from thiazides.

- Treatment? Isotonic saline to restore volume; stop the thiazide.

Hypertonic saline is not indicated here; there are no severe neurologic symptoms, and the main problem is volume depletion.

Case 3: Chronic SIADH from small cell lung cancer

A 62-year-old smoker with known small cell carcinoma presents for routine follow-up. He feels well. Sodium is 122 mEq/L, serum osmolality is low, urine osmolality is inappropriately high, and he appears euvolemic. Prior labs for several months have shown sodium in the low 120s.

- Chronic, asymptomatic, euvolemic hypotonic hyponatremia.

- Endocrine causes need to be ruled out, but malignancy-associated SIADH is likely.

- Best initial management? Fluid restriction and addressing tumor-directed therapy.

- Rapid correction with hypertonic saline is inappropriate here and risks osmotic demyelination.

Organizing these scenarios into mental “types” and mapping each back to your algorithm improves pattern recognition. Over time, you will recognize new vignettes as variations on these themes.

For practice, consider creating your own brief vignettes and flashcards based on missed questions. Many platforms, including MDSteps, allow you to automatically generate flashcard decks from incorrect items and export them to spaced repetition tools. Repeatedly quizzing yourself on “Which branch of the hyponatremia algorithm is this?” cements the framework in long-term memory.

Step 6: High-Yield Boards Pitfalls, Pearls, and Comparisons

Even when students know the basic hyponatremia framework, they often miss questions because of subtle traps. Recognizing these pitfalls in advance can significantly improve your score and your clinical reasoning.

Common pitfalls:

- Treating pseudohyponatremia as real: Low sodium with normal osmolality in a patient with severe hyperlipidemia should not lead to fluid restriction or hypertonic saline. The exam expects you to identify the spurious nature of the value.

- Ignoring glucose correction: In a patient with very high glucose, you must correct sodium before labeling it true hyponatremia. Focusing only on the raw sodium can misdirect you toward unnecessary therapies.

- Overcorrecting chronic cases: The temptation to normalize sodium quickly is a classic error. On exams, when you see chronic, mild-to-moderate symptoms, lean toward slower correction and careful monitoring.

- Missing endocrine causes: Adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism can mimic SIADH. If a vignette features hyponatremia with hypotension, hyperkalemia, or other systemic signs, think beyond SIADH and consider hormonal testing or replacement.

It helps to compare hyponatremia management with other board-favorite electrolyte disorders:

| Disorder | Primary Danger | Correction Theme | USMLE Focus |

| Hyponatremia | Cerebral edema (acute), demyelination (rapid correction) | Balance speed vs safety; limit daily rise | Algorithmic diagnosis, rate of correction |

| Hypernatremia | Cerebral hemorrhage if corrected too fast | Gradual lowering with hypotonic fluids | Water deficit calculation, slow correction |

| Hypokalemia | Arrhythmias, muscle weakness | Identify renal vs extrarenal causes | Drug associations (diuretics, insulin, beta-agonists) |

Another subtle pearl is recognizing when hyponatremia is a bystander versus the primary problem. In some vignettes, sodium is mildly low due to chronic disease and is not the main reason for the patient’s presentation. In that case, the safest exam answer may be to treat the underlying condition (for example, heart failure exacerbation) rather than aggressively correcting sodium.

Continually ask yourself, “What is the exam really testing here?” Often, it is your ability to:

- Interpret labs in context rather than in isolation.

- Distinguish acute emergencies from chronic adaptations.

- Choose interventions that reflect guideline-based correction rates.

Building this kind of judgment is easiest when you have detailed performance analytics. A strong dashboard, like the exam readiness view in MDSteps, can highlight whether you struggle more with electrolyte diagnosis, fluid selection, or rate-of-correction decisions, guiding your targeted review.

Rapid-Review Checklist and Exam-Day Essentials for Sodium Disorders

In the final days before your exam, you want a compact mental script for sodium questions. Use this rapid-review checklist as a last-minute run-through any time you see hyponatremia in a vignette.

Rapid-Review Checklist: Hyponatremia Algorithm

- 1. Confirm the lab: Repeat if suspicious, correct for hyperglycemia, and check serum osmolality.

- 2. Categorize osmolality: Hypotonic vs isotonic (pseudo) vs hypertonic (glucose, mannitol).

- 3. Assess volume status: Hypovolemic, euvolemic, or hypervolemic using exam findings.

- 4. Use urine studies: Urine sodium and osmolality to distinguish renal vs extrarenal loss and SIADH vs polydipsia.

- 5. Evaluate symptoms and time course: Mild vs moderate vs severe; acute vs chronic.

- 6. Choose treatment branch: Hypertonic saline for acute severe; isotonic saline for hypovolemia; restriction +/- diuretics for euvolemic or hypervolemic states.

- 7. Respect correction limits: Aim generally for ≤ 8–10 mEq/L per 24 hours, lower in high-risk patients.

- 8. Watch for overcorrection: If sodium rises too quickly in chronic cases, consider re-lowering with hypotonic fluids and desmopressin.

- 9. Remember endocrine causes: Evaluate for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism when the picture is not straightforward.

- 10. Treat the underlying disease: CHF, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, malignancy, and medications all drive long-term management.

On exam day, do not let a low sodium value distract you from the rest of the vignette. Integrate it into the overall story: Is this the explanation for the neurologic symptoms, or just a chronic lab abnormality? Is the immediate priority airway and breathing, or is there time to think about slow correction? Answering those questions quickly and calmly is a sign that you have internalized the algorithm.

If you want to solidify this topic further, consider building a short personal cheat sheet with your own words and a simple flowchart. Many learners find it helpful to sketch a one-page diagram: serum osmolality at the top, branching into hypotonic versus others, then volume status, then therapy. Reviewing that diagram in the days before the test can anchor your thinking and reduce cognitive load when you are under time pressure.

Finally, remember that sodium problems are rarely isolated. They intersect with fluid resuscitation decisions, endocrine disorders, kidney disease, and neurologic emergencies. Mastering sodium disorders for USMLE will therefore strengthen your performance across multiple disciplines, turning what might feel like an intimidating topic into a reliable source of points.

References

Medically reviewed by: Alex Morgan, MD, FACP – Board-Certified Internal Medicine

100+ new students last month.