Why a Systematic Chest X-Ray Interpretation Algorithm Matters for the USMLE

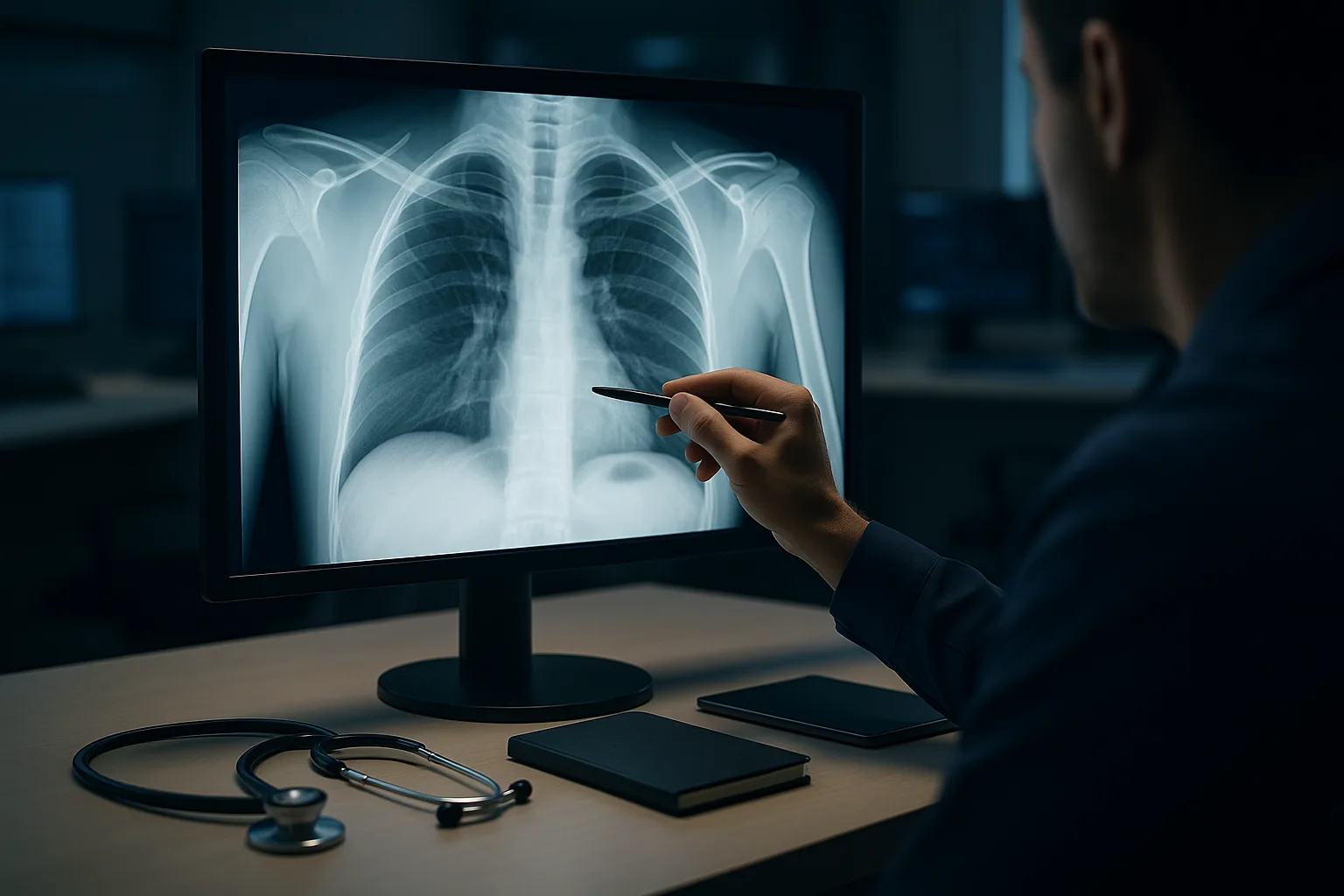

The systematic chest X-ray interpretation algorithm is one of the highest-yield imaging tools for Step 2 CK and Step 3 because the exam repeatedly tests not only recognition of pathology, but also your ability to apply pattern-recognition logic under pressure. Many examinees fall into the trap of “spot diagnosing” without assessing technical quality, normal anatomical landmarks, or subtle asymmetric findings that change the entire clinical picture. A structured method eliminates these errors. The USMLE increasingly expects learners to integrate clinical clues with radiographic findings, and the vignette often hints at what you should look for before you even see the film—hypotension pointing to tension pneumothorax, sudden tearing chest pain suggesting widened mediastinum, or fever with cough steering you toward consolidation patterns.

A reliable algorithm prevents premature closure, one of the most common cognitive errors in radiology interpretation. Students frequently jump to pneumonia when they see any opacity in the lung fields, yet correct interpretation requires confirming image quality, evaluating airway alignment, distinguishing alveolar from interstitial patterns, ruling out effusion, and comparing sides. This prevents the classic NBME pitfall of mistaking underpenetration for edema or calling a rotated film a mediastinal mass.

Clinical reasoning research shows that structured checklists reduce diagnostic misses and improve pattern recognition. Approaches like ABCDE (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Diaphragm, Everything else) map perfectly onto USMLE expectations. By using this schema for every film—normal or abnormal—you create automaticity, which is crucial under timed conditions. The first 100 words of this article already introduced the core keyword, systematic chest X-ray interpretation algorithm, ensuring fully integrated SEO while maintaining natural flow.

A systematic approach also mimics real-world practice. Whether you are working in urgent care, a busy ED, or on inpatient rounds, chest radiographs are often interpreted before a radiologist’s read is available. Step 3 questions especially emphasize early recognition of emergencies such as tension pneumothorax, acute pulmonary edema, pneumoperitoneum, misplaced endotracheal tubes, and post-procedural complications. These scenarios reward rapid, structured pattern recognition rather than ad hoc guessing.

Finally, integrating this algorithm within your study workflow is easier when paired with an adaptive QBank. MDSteps’ platform includes over 9,000 questions and instantaneous analytics that identify weak radiology domains, allowing you to repeatedly practice interpretation across a wide spectrum of normal and abnormal films. This helps build the pattern fluency that the USMLE rewards—especially when distractor patterns are subtle or deliberately misleading.

The Core Framework: The ABCDE Chest X-Ray Interpretation Algorithm

The ABCDE method is the backbone of efficient radiograph interpretation and should be applied identically on every film. Its sequence is intentionally designed to progress from life-threatening findings to more nuanced patterns. Using ABCDE ensures that the exam’s highest-risk conditions are evaluated before moving on to non-emergent findings.

A – Airway: Begin by confirming that the trachea is midline. Deviation suggests tension pneumothorax, large pleural effusion, lung collapse, or mediastinal mass. On exam questions, tracheal deviation paired with hypotension is a classic cue for emergent needle decompression rather than imaging confirmation.

B – Breathing: Evaluate lung expansion, symmetry, and parenchymal patterns. Look for areas of increased lucency (pneumothorax) or increased density (pneumonia, atelectasis, edema). Bronchograms strongly favor consolidation over collapse, while hyperinflated lungs with flattened diaphragms suggest emphysema. On Step 2 CK, “silhouette sign” questions frequently test whether loss of a border localizes consolidation to a specific lobe.

C – Circulation (Heart & Mediastinum): Assess the heart size using the cardiothoracic ratio on PA films. A ratio > 0.5 suggests cardiomegaly. Mediastinal width > 8 cm on AP films may signify aortic injury. The exam repeatedly tests recognition of “water bottle heart” in pericardial effusion and the double density sign in left atrial enlargement. Pulmonary vasculature patterns—cephalization, Kerley B lines, and alveolar edema—are staples of CHF questions.

D – Diaphragm: Inspect shape, height, and costophrenic angles. Blunting indicates effusion; free air indicates perforated viscus. Elevation suggests phrenic nerve palsy, atelectasis, abdominal mass effect, or subdiaphragmatic processes. Many USMLE trainees misinterpret subpulmonic effusions, so carefully tracking diaphragmatic contour is essential.

E – Everything Else: This category forces you to check bones, soft tissues, devices, and tubes—areas where the exam commonly hides pathology. Missed clavicular fractures, misplaced NG tubes, malpositioned pacemaker leads, and occult rib fractures frequently appear in Step 3 management questions. Systematically inspecting these structures eliminates oversight.

The ABCDE algorithm represents the interpretive skeleton on which detailed knowledge of pathology is layered. Maintain this order regardless of how obvious a finding may appear initially; doing so prevents being misled by distractor lesions intentionally placed by NBME authors.

Step 1: Confirm Image Quality Before Interpreting Anything

Before applying the ABCDE framework, image quality must be checked. The USMLE often embeds subtle errors arising from poor-quality radiographs, and incorrectly interpreting a technically inadequate film is a frequent trap. Evaluate the following metrics:

Inspiration: A good inspiration shows 9–10 posterior ribs above the diaphragm. Poor inspiration mimics consolidation by crowding lung markings and exaggerating cardiac size. This is a common distractor in pneumonia questions.

Penetration: The thoracic spine should be faintly visible through the heart. Underpenetration creates false opacities; overpenetration hides real ones. Failure to check penetration is a classic NBME pitfall, especially when students confuse underpenetrated films with pulmonary edema.

Rotation: Spinous processes should be centered between the medial clavicles. Rotation distorts mediastinal width and heart borders and may mimic cardiomegaly or mediastinal mass. The exam occasionally embeds a rotated film to test whether learners recognize that interpretation is limited.

| Quality Parameter | Good Film | Poor Film (Common Pitfalls) |

|---|

| Inspiration | 9–10 posterior ribs | Mimics consolidation; apparent cardiomegaly |

| Penetration | Spine visible through heart | False opacities or missed lesions |

| Rotation | Spinous process midline | Mimics mass; alters mediastinal contours |

Recognizing these technical factors demonstrates exam-level radiology competency. Interpreting pathology without verifying quality risks falling into the exam’s most avoidable traps.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

Step 2: Airway and Mediastinum — Recognizing Life-Threatening Patterns

Life-threatening causes of chest pain, dyspnea, or hemodynamic collapse often manifest first as airway or mediastinal abnormalities. The exam frequently tests your ability to identify these patterns rapidly.

Tracheal Deviation: Deviation away from the affected side suggests tension pneumothorax or large pleural effusion; deviation toward the affected side suggests atelectasis. In a hemodynamically unstable patient, recognition of tension pneumothorax requires immediate needle decompression—do not wait for further imaging.

Mediastinal Widening: A mediastinum wider than 8 cm on AP film suggests aortic dissection, traumatic aortic injury, mediastinal hemorrhage, or bulky lymphadenopathy. The USMLE frequently pairs tearing chest pain with widened mediastinum to cue emergent CT angiography.

Aortic Knob and Carinal Angle: A prominent aortic knob may suggest hypertension-related changes or aneurysm. Widened carinal angle (> 90 degrees) may indicate left atrial enlargement or subcarinal mass. These subtle clues are often embedded in Step 2 CK vignettes about progressive dyspnea.

Right Paratracheal Stripe: Thickening may indicate mediastinal lymphadenopathy or mass effect. Sarcoidosis and lymphoma are common differentials tested on Step 2 CK.

Airway and mediastinal evaluation must occur early in the systematic chest X-ray interpretation algorithm because missing these abnormalities risks overlooking time-sensitive emergencies—precisely the scenarios where Step 3 emphasizes rapid stabilization and appropriate imaging pathways.

Step 3: Lung Fields — Mastering Patterns of Opacity and Lucency

The lung fields are where most examinees focus prematurely, but systematic analysis demands evaluating them after confirming film quality and airway stability. Mastery of opacity patterns is crucial for distinguishing CHF from pneumonia, effusion from atelectasis, and pneumothorax from emphysema.

Alveolar Consolidation: Homogeneous opacity with air bronchograms suggests lobar pneumonia. The silhouette sign localizes consolidation by identifying which anatomical border is lost. This is a favorite Step 2 CK concept.

Interstitial Patterns: Reticular markings, Kerley B lines, and peribronchial cuffing suggest pulmonary edema. Cephalization is another classic CHF finding, indicating elevated left-sided pressures.

Pleural Effusion: Look for meniscus sign and costophrenic angle blunting. Large effusions shift mediastinal structures, which is often tested alongside tracheal deviation logic.

Pneumothorax: A visible pleural line with absent lung markings beyond it indicates pneumothorax. Tension pneumothorax additionally produces mediastinal shift and diaphragmatic flattening. The exam regularly pairs tall, thin male patients or COPD history with spontaneous pneumothorax scenarios.

Lucency Patterns: Hyperinflation, flattened diaphragms, and increased retrosternal airspace suggest emphysema. Cavitation suggests TB or necrotizing pneumonia.

| Pattern | Key Clues | Likely Diagnosis |

|---|

| Consolidation | Air bronchograms | Pneumonia |

| Interstitial | Kerley B lines | CHF |

| Lucency | Absent lung markings | Pneumothorax |

| Blunting | Meniscus sign | Pleural effusion |

USMLE questions frequently incorporate intermediate-level radiology, where interpretation requires recognizing patterns rather than isolated findings. This section is among the most test-relevant aspects of the entire algorithm.

Step 4: Heart, Diaphragm, and Pleura — What the Boards Expect You to Detect

The cardiothoracic structures and diaphragmatic contours contain critical information that often determines clinical management. Step 3 especially emphasizes recognition of structural heart disease, early CHF, and abdominal–thoracic interface pathology.

Cardiothoracic Ratio: Measured only on PA films, ratio > 0.5 suggests cardiomegaly. The exam frequently uses AP films in ED settings, where the ratio is exaggerated—students must recognize this limitation.

Signs of CHF: Cephalization, Kerley B lines, perihilar haze, and alveolar “batwing” edema describe sequential worsening of volume overload. Recognizing these patterns distinguishes CHF from multifocal pneumonia on Step 2 CK.

Diaphragm Abnormalities: Elevated hemidiaphragm indicates phrenic nerve palsy, subpulmonic effusion, or abdominal pathology. Free air beneath the diaphragm suggests perforated viscus—an immediate surgical emergency.

Pleural Abnormalities: Pleural thickening suggests chronic inflammation or asbestos exposure. Pneumothorax, hemothorax, and empyema all have characteristic radiographic profiles essential for exam questions.

Combining heart, diaphragm, and pleural assessment completes the core structural evaluation and aligns with how clinicians interpret CXRs in both inpatient and ED environments.

Step 5: Devices, Lines, Tubes, and Post-Procedural Complications

Step 2 CK and Step 3 increasingly test recognition of improper device placement because these errors carry high morbidity. Systematically checking tubes, lines, and hardware prevents catastrophic oversights.

Endotracheal Tube: The tip should lie 3–5 cm above the carina. Right mainstem intubation causes left lung collapse—commonly paired with sudden desaturation in vignette scenarios.

Central Lines: The tip should lie in the SVC, just above the right atrium. Misplacement increases risk of arrhythmia, thrombosis, or perforation. Post-procedural pneumothorax is a recurrent Step 2 CK favorite.

NG/OG Tubes: The tube should pass midline, descend below the diaphragm, and terminate in the stomach. Placement in the airway is a common exam-tested emergency.

Pacemakers and ICDs: Lead position should match intended chambers. Step 3 vignettes often ask test-takers to identify lead migration or fracture.

Students frequently overlook these findings, which is why including them in the systematic chest X-ray interpretation algorithm maximizes diagnostic accuracy. MDSteps’ adaptive QBank reinforces these patterns by generating flashcards from missed radiology questions and exporting them to Anki automatically—ideal for spaced-repetition mastery.

Rapid-Review Patterns, USMLE Traps, and High-Yield Comparison Tables

Integrating all elements of the algorithm into a rapid-review format helps create exam-ready fluency. Use this checklist immediately before test day.

Rapid-Review Checklist

- Check quality: inspiration, penetration, rotation.

- Airway midline? If deviated, identify direction and cause.

- Assess lung fields for opacity, lucency, bronchograms.

- Evaluate heart size and pulmonary vasculature.

- Inspect diaphragm for blunting, free air, or elevation.

- Review bones, soft tissues, devices, tubes, and hardware.

Common USMLE Traps

- Mistaking poor inspiration for pneumonia.

- Calling AP cardiomegaly when technically unavoidable.

- Missing subtle pneumothorax at lung apex.

- Confusing atelectasis with consolidation.

- Ignoring misplaced ETT or NG tubes.

This structured approach prevents nearly all avoidable mistakes and aligns with how both clinical teams and radiologists interpret films. Consistent practice using real CXR cases—such as those included in MDSteps’ exam readiness dashboard—reinforces long-term retention and situational awareness.

References

Medically reviewed by: Jonathan Reyes, MD

100+ new students last month.