Understanding the Upper vs Lower GI Bleed Algorithm

Mastering the distinction between an upper and lower gastrointestinal bleed is a core Step 2 CK expectation, because the first 5–10 minutes of management determine patient survival and test performance. The phrase “upper vs lower GI bleed algorithm” reflects two overlapping diagnostic funnels: one driven by hemodynamics, the other by anatomic source prediction. This opening section provides foundational definitions, early differentials, and the decision logic that underpins every USMLE-style GI bleed vignette.

On Step 2 CK, a GI bleed question is rarely about naming melena versus hematochezia. Instead, the exam tests your ability to stabilize the patient, identify red flags, decide imaging vs endoscopy vs medical therapy, and apply clinical probability based on vitals, stool description, labs, medications, and risk factors. The core algorithm centers on three pillars:

- (1) Anatomy — upper GI bleeds arise proximal to the ligament of Treitz; lower bleeds arise distal to it.

- (2) Clinical appearance — melena commonly suggests an upper-source, whereas brisk lower sources can mimic upper bleeds.

- (3) Hemodynamic status — this determines whether you perform immediate resuscitation, NG lavage, CTA, or endoscopic evaluation.

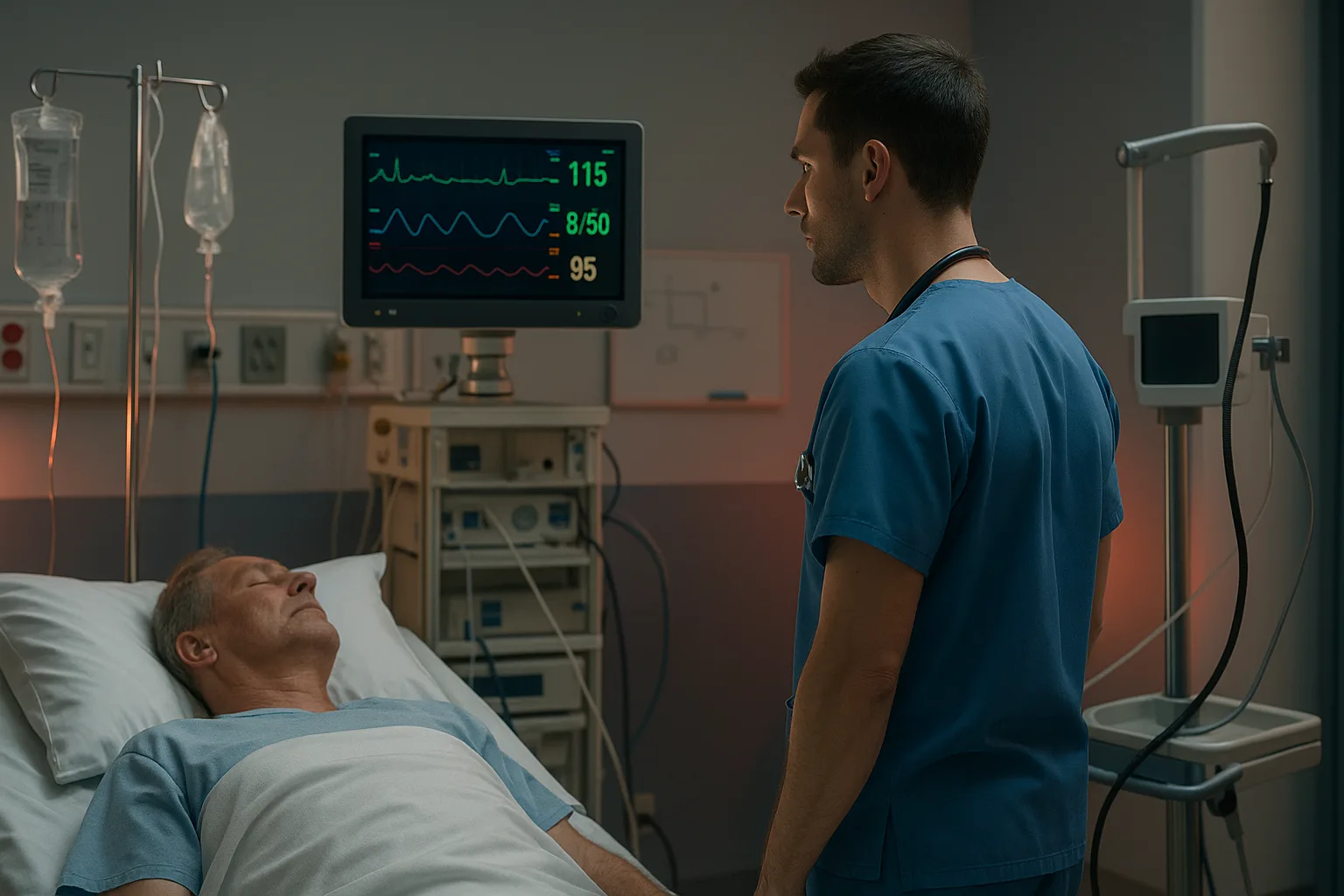

Because the exam frames management around acute stabilization, Step 2 CK questions often include borderline hypotension, tachycardia, orthostasis, or early hypovolemic shock. Identifying when to activate massive transfusion protocol, when to use 2 large-bore IVs, and when to prioritize airway protection over diagnostic testing is central to scoring high in emergency stabilization domains.

Your exam approach begins with recognition patterns: hematemesis is almost always an upper bleed; maroon stools may reflect the right colon or small bowel; and melena generally indicates bleeding above the colon, though 10–15% of fast lower bleeds can mimic it. Vignettes may also test the use of medications such as PPIs, octreotide, prophylactic antibiotics for cirrhotics, or the indications for endoscopic therapy versus IR embolization.

The remainder of this article builds the complete clinical pathway: initial stabilization, risk stratification, diagnostic sequencing, endoscopic vs radiologic therapy, disposition decisions, and high-yield exam traps. At the end, you’ll find a rapid-review checklist summarizing all essential algorithmic steps.

Algorithm Step 1: Hemodynamic Stability and Immediate Resuscitation

The first branch of the upper vs lower GI bleed algorithm is always stabilization. Every Step 2 CK vignette begins with airway, breathing, circulation (ABCs). When hypotension or altered mental status is present, airway protection precedes diagnostic workup.

High-yield stabilization steps include:

- Airway: Intubate for active hematemesis, altered mental status, or inability to protect airway.

- Access: Place two large-bore (16–18 gauge) IV lines immediately.

- Fluids: Give 1–2 L crystalloid for hypotension, then transition to blood products as needed.

- Massive transfusion protocol: Initiate with 1:1:1 PRBCs:FFP:platelets if unstable despite fluids.

- Type and cross: Order at least 4–6 units in brisk bleeds.

- Reverse anticoagulation: Use PCC for warfarin; andexanet alfa or PCC for factor Xa inhibitors; idarucizumab for dabigatran.

USMLE questions often provide subtle clues such as “cool extremities,” “delayed capillary refill,” or “SBP in the high 80s.” Your response should be immediate stabilization, not endoscopy or NG lavage. If you do not stabilize the patient first, the answer is wrong—even if the diagnostic test is ultimately needed later.

| Hemodynamic Status |

Initial Action |

Next Step |

| Stable (normal BP, normal mentation) |

IV access, CBC, type & screen, PPI |

Risk stratify → early endoscopy |

| Borderline (tachycardia, orthostasis) |

IV fluids + labs |

Admit, monitor, prep for scope |

| Unstable (SBP < 90, AMS) |

Airway, large-bore IVs, MTP |

Stabilize → emergent intervention |

USMLE trap: If the patient is unstable, never choose “CT angiography,” “colonoscopy,” or “capsule endoscopy” before stabilization. Only after achieving a safe hemodynamic status should diagnostic steps proceed.

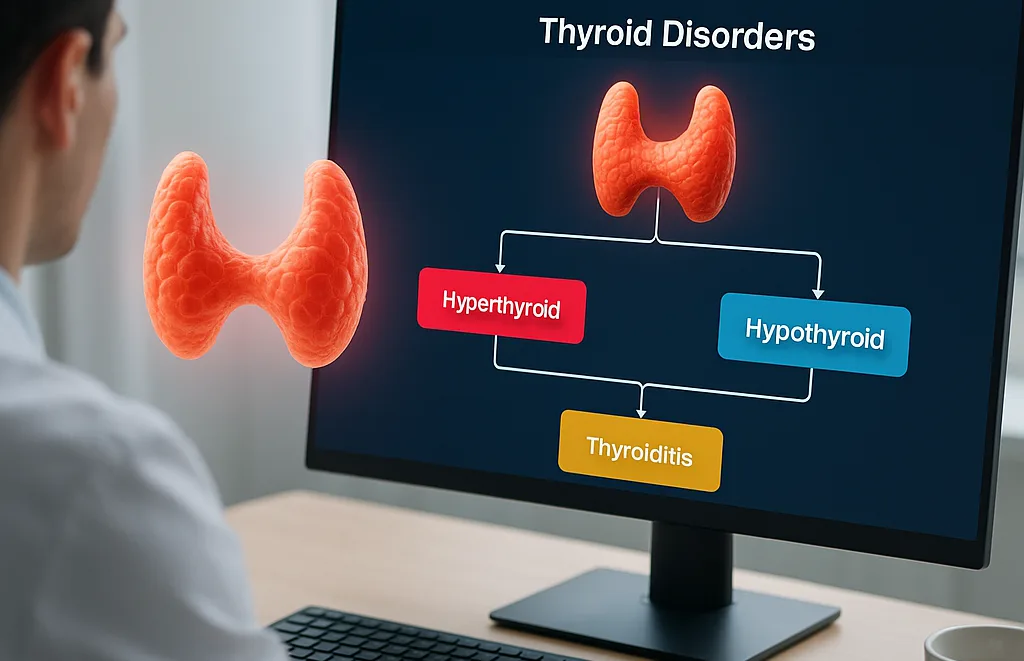

Algorithm Step 2: Predicting the Source – Clinical Clues for Upper vs Lower

Once stabilized, the algorithm turns to identifying the probable site of bleeding. On Step 2 CK, pattern recognition is king: stool description, medications, comorbidities, and symptom timing all hint at the bleeding source.

Classic upper GI bleed features include:

- Hematemesis (bright red or coffee-ground)

- Melena (black, tarry stool)

- History of PUD, NSAIDs, H. pylori, prior ulcers

- Cirrhosis with portal hypertension

- Recent retching → suspect Mallory-Weiss tear

- Shock with significant BUN elevation (BUN:Cr ratio > 30)

Classic lower GI bleed features include:

- Hematochezia (bright red stool)

- Painless bleeding → think diverticulosis

- Post-radiation colitis or inflammatory bowel disease

- Angiodysplasia in older adults

- Cancer or polyps causing chronic slow bleeding

However, the exam often challenges assumptions:

- Rapid upper GI bleeds can present with bright red blood per rectum.

- Slow right-sided colonic bleeds can cause melena.

- Small bowel bleeds may mimic either pattern.

This is where clinical reasoning matters. Factors like cirrhosis, NSAID use, or prior ulcer history heavily tilt toward an upper bleed even if the stool looks bright red. Similarly, older adults with known diverticulosis and a normal BUN:Cr ratio are more likely to have a lower bleed.

Algorithm logic for prediction:

- If hematemesis → upper until proven otherwise.

- If melena → upper > lower (roughly 90% upper on exams).

- If hematochezia + stable → lower most likely.

- If hematochezia + unstable → suspect brisk upper bleed.

This predictive phase informs which diagnostic test you pursue next: EGD for upper sources, colonoscopy or CTA for lower, or capsule endoscopy when standard testing fails to localize the source.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

Algorithm Step 3: Laboratory & Risk Stratification Tools

Laboratory evaluation is integrated into the upper vs lower GI bleed algorithm to grade severity, identify comorbid risks, and predict the need for intervention. On Step 2 CK, you must interpret labs quickly and know which values change earliest after acute blood loss.

Essential labs in all GI bleeds:

- CBC (hemoglobin may be normal early)

- Type & screen or type & cross

- Coagulation profile (INR, PT/PTT)

- BMP (BUN elevation suggests upper bleed)

- LFTs (evaluate for cirrhosis and variceal risk)

- Lactate (marker of shock physiology)

High-yield lab patterns:

- BUN disproportionately elevated → strongly favors upper GI bleed.

- Rapid hemoglobin drop → severe active bleed.

- Elevated INR → correct before endoscopy if >1.5–1.6.

- Platelets <50k → transfuse prior to procedures.

Next, apply risk scoring. While Step 2 CK does not expect memorization of full scoring systems, you should know when a patient is “low risk” versus “high risk.” The Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS) predicts the need for medical intervention in upper GI bleed, while Rockall helps predict mortality post-endoscopy.

General exam-relevant rules:

- Stable vitals + no comorbidities + minor bleeding → early outpatient endoscopy may be acceptable.

- Unstable vitals + multiple comorbidities + active bleeding → ICU admission & urgent scope.

At this stage in clinical management, many students using MDSteps’ adaptive QBank find it helpful to integrate spaced recall flashcards that automatically sync with missed questions involving lab-based risk clues. This reinforces recognition of patterns such as BUN elevation, INR abnormalities, and the early normal-hemoglobin pitfall common in acute bleeding.

Algorithm Step 4: Diagnostic Sequencing – EGD, Colonoscopy, CTA, or Capsule?

Once stabilized and preliminarily classified as upper vs lower, the algorithm moves to definitive diagnostic evaluation. Step 2 CK frequently asks the “next best test” after initial stabilization, making this phase high-yield.

Upper GI bleed suspected → First test = EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy).

This is done emergently (within 24 hours) for most patients, and immediately in unstable patients after resuscitation. EGD allows visualization and endoscopic therapy such as clipping, cautery, epinephrine injection, or band ligation for varices.

Lower GI bleed suspected & stable → First test = colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy requires bowel prep, so it is not used in unstable patients with massive bleeding. Instead, unstable patients require CT angiography or interventional radiology evaluation.

If patient is unstable with hematochezia → CTA FIRST to rule out brisk upper source or localize site.

This is a classic Step 2 CK trap. CTA is fast, noninvasive, and highly sensitive for active bleeding. It guides embolization via interventional radiology.

Capsule endoscopy is used when both EGD and colonoscopy fail to identify the source, suggesting a small bowel bleed.

| Clinical Scenario |

Next Best Test |

| Suspected upper bleed (melena, hematemesis) |

EGD |

| Stable hematochezia |

Colonoscopy |

| Unstable hematochezia |

CTA → IR embolization |

| EGD + colonoscopy negative |

Capsule endoscopy |

Memorizing this sequencing ensures you consistently select the correct “next best step” answer choices on the exam, where timing and stability determine the preferred diagnostic test.

Algorithm Step 5: Management of Upper GI Bleeds (Ulcers, Varices, Mallory-Weiss)

Management diverges significantly based on the bleeding source.

Peptic ulcer bleeding is the most common upper-source cause. Management includes:

- High-dose PPI therapy (IV PPI drip or intermittent bolus)

- Endoscopic therapy (epinephrine injection + clip or cautery)

- Repeat endoscopy for rebleeding

- Treat H. pylori if identified

Variceal bleeding requires a specific bundle of therapy:

- Octreotide IV — reduces portal pressure

- Prophylactic antibiotics — ceftriaxone to prevent SBP

- Band ligation via endoscopy

- TIPS for refractory bleeding unresponsive to banding + medical therapy

- Hold beta-blockers during acute variceal bleed

Mallory-Weiss tears often stop spontaneously; treat with PPIs ± endoscopic therapy if bleeding persists. Boerhaave syndrome (esophageal rupture) presents with severe chest pain and crepitus; it is a surgical emergency.

Stress gastritis and erosive esophagitis are additional sources tested on Step 2 CK.

Algorithm Step 6: Management of Lower GI Bleeds (Diverticulosis, Angiodysplasia, IBD, Cancer)

Lower GI bleeding has different etiologies and different exam-relevant management steps.

Diverticular bleeding is the most common cause of acute painless hematochezia. Management includes:

- Stabilization

- Colonoscopy with endoscopic therapy (clipping or cautery)

- CTA → embolization if unstable or colonoscopy unsuccessful

Angiodysplasia causes intermittent painless bleeding in older adults, especially those with aortic stenosis or ESRD (Heyde syndrome). Therapy involves colonoscopic cautery; refractory cases may require IR embolization.

Inflammatory bowel disease causes chronic bleeding with abdominal pain and diarrhea. Manage with steroids for flares, biologics for maintenance, and colonoscopy for surveillance.

Colon cancer causes chronic slow blood loss, iron-deficiency anemia, and occasionally visible bleeding. Vignettes often include unintentional weight loss or change in bowel habits.

Hemorrhoids cause bright red blood on toilet paper — extremely low risk and easily distinguished in exam scenarios.

When preparing for these distinctions, many MDSteps users rely on the adaptive analytics dashboard, which tracks errors across GI bleed etiologies and automatically generates flashcards from missed questions, exporting them directly to Anki for reinforcement.

High-Yield Step 2 CK Traps, Red Flags, and Clinical Pearls

Here are the most testable pitfalls and clinical pearls related to the upper vs lower GI bleed algorithm:

- Never give beta-blockers during acute variceal bleeding.

- Always give prophylactic antibiotics for variceal bleeds.

- Massive hematochezia in an unstable patient = likely upper GI source.

- Correct INR and platelets before endoscopy.

- BUN elevation strongly favors upper GI bleeding.

- Acute hemoglobin will not fall immediately.

- If both EGD and colonoscopy negative → small bowel evaluation (capsule).

- CTA is first step for unstable lower-suspected bleeding.

Red flags requiring emergent action:

- SBP < 90

- Altered mental status

- Large-volume hematemesis

- Bright red rectal bleeding + shock

- Signs of cirrhosis with variceal risk

Rapid-Review Checklist

- Stabilize first: airway → large-bore IVs → fluids/blood → correct coagulopathy.

- Upper clues: hematemesis, melena, elevated BUN, NSAIDs, cirrhosis.

- Lower clues: hematochezia, diverticulosis, angiodysplasia, IBD.

- Test sequencing: EGD for upper; colonoscopy for stable lower; CTA for unstable lower.

- Therapy: PPI for ulcers; octreotide + antibiotics for varices; IR embolization for refractory bleeds.

- Next-best-step logic heavily depends on stability.

Medically reviewed by: Jonathan Reeds, MD (Gastroenterology)

References

100+ new students last month.