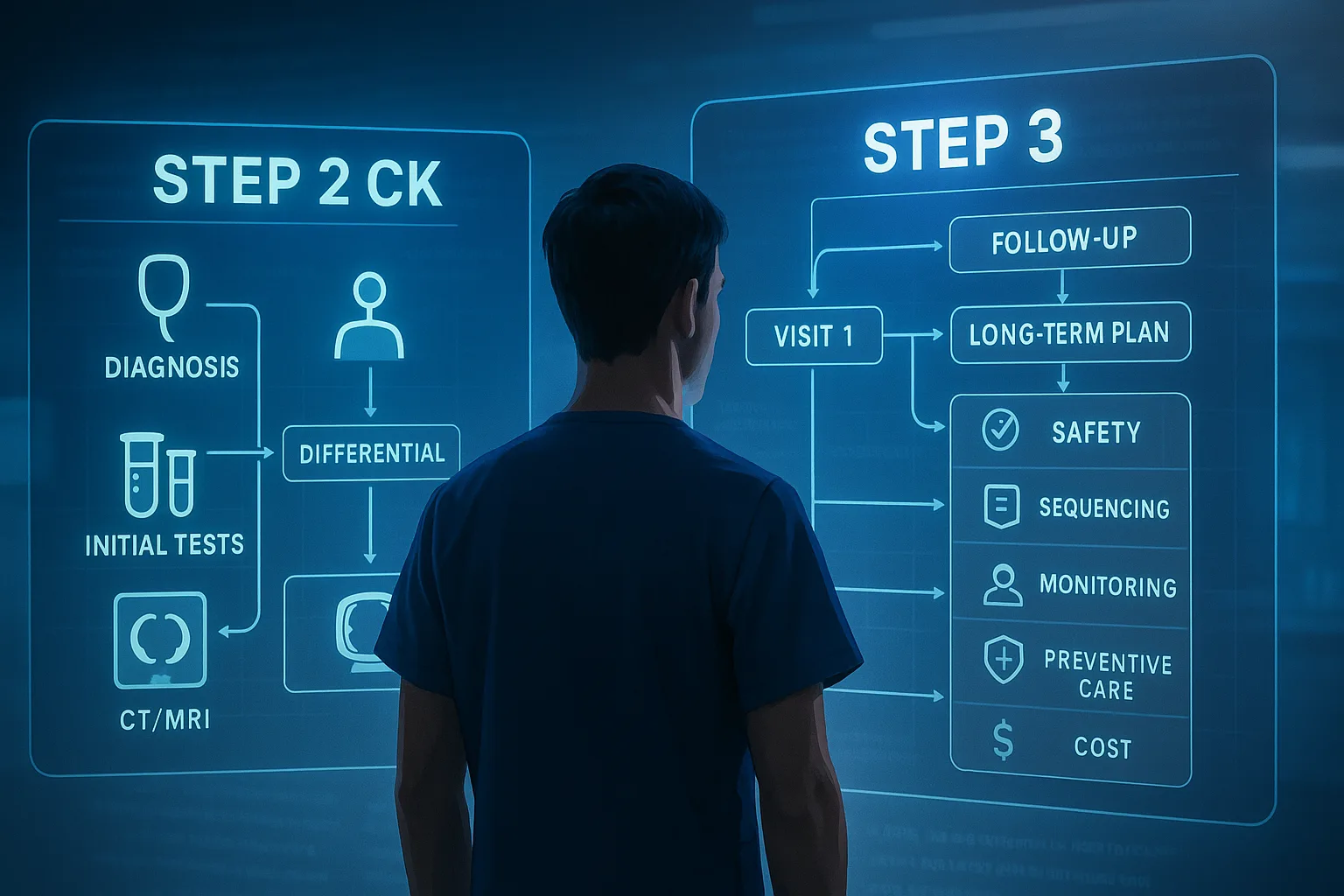

1. Exam Orientation and Stroke Presentation

On USMLE Step 3, acute ischemic stroke questions frequently simulate the high-stakes decision-making of the emergency department. The core testing strategy is recognizing “time is brain” — the faster reperfusion occurs, the better the neurological outcome. Candidates are expected to rapidly identify ischemic stroke syndromes, apply imaging protocols, and determine eligibility for intravenous thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy. The emphasis is less on esoteric vascular neuroanatomy and more on prioritizing first actions that directly alter morbidity and mortality.

Classic vignettes involve an elderly patient with sudden focal deficits such as right-sided weakness and aphasia, last seen normal within a few hours. Step 3 questions probe whether the candidate correctly orders an immediate non-contrast head CT to exclude hemorrhage before initiating therapy. Distractors include ordering MRI or carotid Doppler before CT, which delay critical interventions. Examiners may embed subtle timing cues — “symptom onset 90 minutes ago” versus “symptom onset 10 hours ago” — to test the candidate’s knowledge of therapeutic windows.

Initial stabilization is also tested. Ensure airway, breathing, and circulation are intact, establish IV access, check blood glucose (hypoglycemia mimics stroke), and perform a rapid neurologic exam. Vignettes occasionally include hypertensive emergencies, arrhythmias, or seizures as stroke mimics. Recognizing these pitfalls and correcting reversible causes is as important as initiating reperfusion therapy. By keeping onset time, imaging, and contraindications in mind, candidates can navigate Step 3 stroke questions efficiently.

2. Pathophysiology and Mechanisms of Ischemic Stroke

Ischemic stroke occurs when cerebral blood flow is interrupted, leading to neuronal energy failure, ionic imbalance, and excitotoxicity. Within minutes, ATP depletion triggers Na⁺/K⁺ pump failure, cytotoxic edema, and release of glutamate, which propagates calcium influx and free radical injury. The ischemic core undergoes rapid necrosis, while the surrounding “penumbra” retains partial perfusion and remains salvageable if blood flow is restored. Step 3 often tests recognition that reperfusion therapies target this penumbra to improve outcomes.

Stroke etiologies vary. Cardioembolic sources (atrial fibrillation, LV thrombus, valvular disease) account for large cortical infarcts with sudden maximal deficits. Large artery atherosclerosis (carotid stenosis, vertebral occlusion) produces territorial infarcts, while small vessel lipohyalinosis causes lacunar syndromes (pure motor or sensory deficits). Examiners may frame vignettes to differentiate these based on onset, risk factors, and deficits.

Hemorrhagic transformation is a feared complication of reperfusion therapy. This risk underpins the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase. In addition, cerebral autoregulation is impaired during acute ischemia; thus, aggressive BP reduction before tPA is contraindicated, as cerebral perfusion may worsen. These mechanistic underpinnings explain why guidelines emphasize maintaining systolic BP below 185 mmHg prior to thrombolysis but otherwise avoiding precipitous reductions.

3. ED Workflow and Imaging Algorithm

Emergency management hinges on rapid triage and diagnostic sequencing. Time of symptom onset must be established immediately — either witnessed onset or last known well. Patients then undergo rapid neurologic evaluation, often quantified with the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Concurrently, non-contrast head CT is obtained within 20–25 minutes of arrival to exclude intracerebral hemorrhage. MRI diffusion-weighted imaging is more sensitive but not appropriate in the acute decision-making window.

Additional labs (CBC, PT/INR, glucose, renal function, electrolytes) are drawn but should not delay tPA if no contraindications are suspected. Step 3 emphasizes that glucose must be checked at bedside to rule out hypoglycemia. ECG and troponins may reveal atrial fibrillation or myocardial infarction but are secondary to the immediate CT scan.

| Step |

Target Time (Door-to-Action) |

Purpose |

| Initial physician evaluation |

≤10 minutes |

Rapid assessment, ABCs, NIHSS |

| Non-contrast head CT |

≤25 minutes |

Exclude hemorrhage |

| CT interpreted |

≤45 minutes |

Guide reperfusion eligibility |

| tPA administration |

≤60 minutes |

Optimize outcomes |

The “door-to-needle” goal of under 60 minutes is frequently tested. Questions may penalize ordering unnecessary tests (e.g., carotid duplex) that delay this critical benchmark.

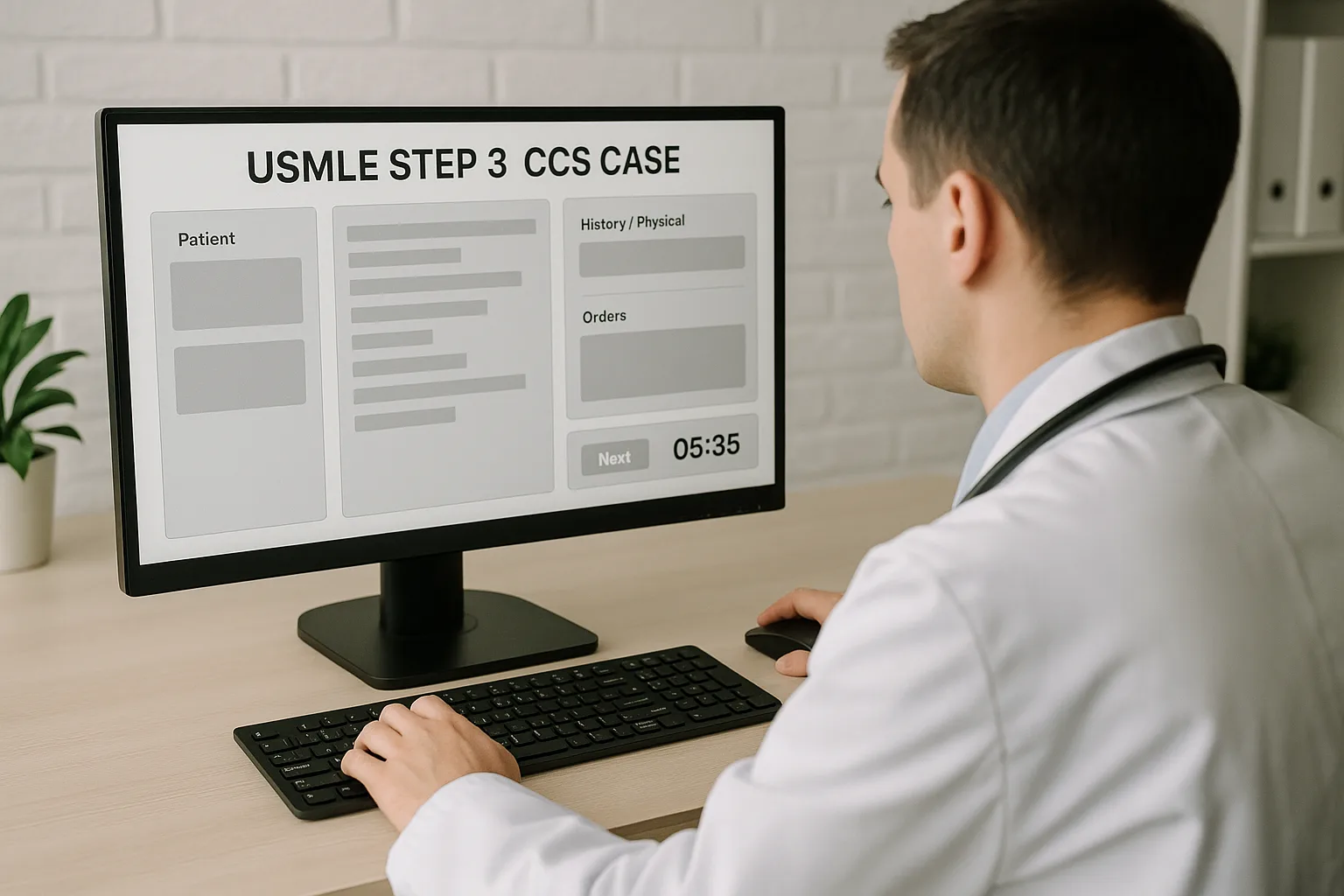

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

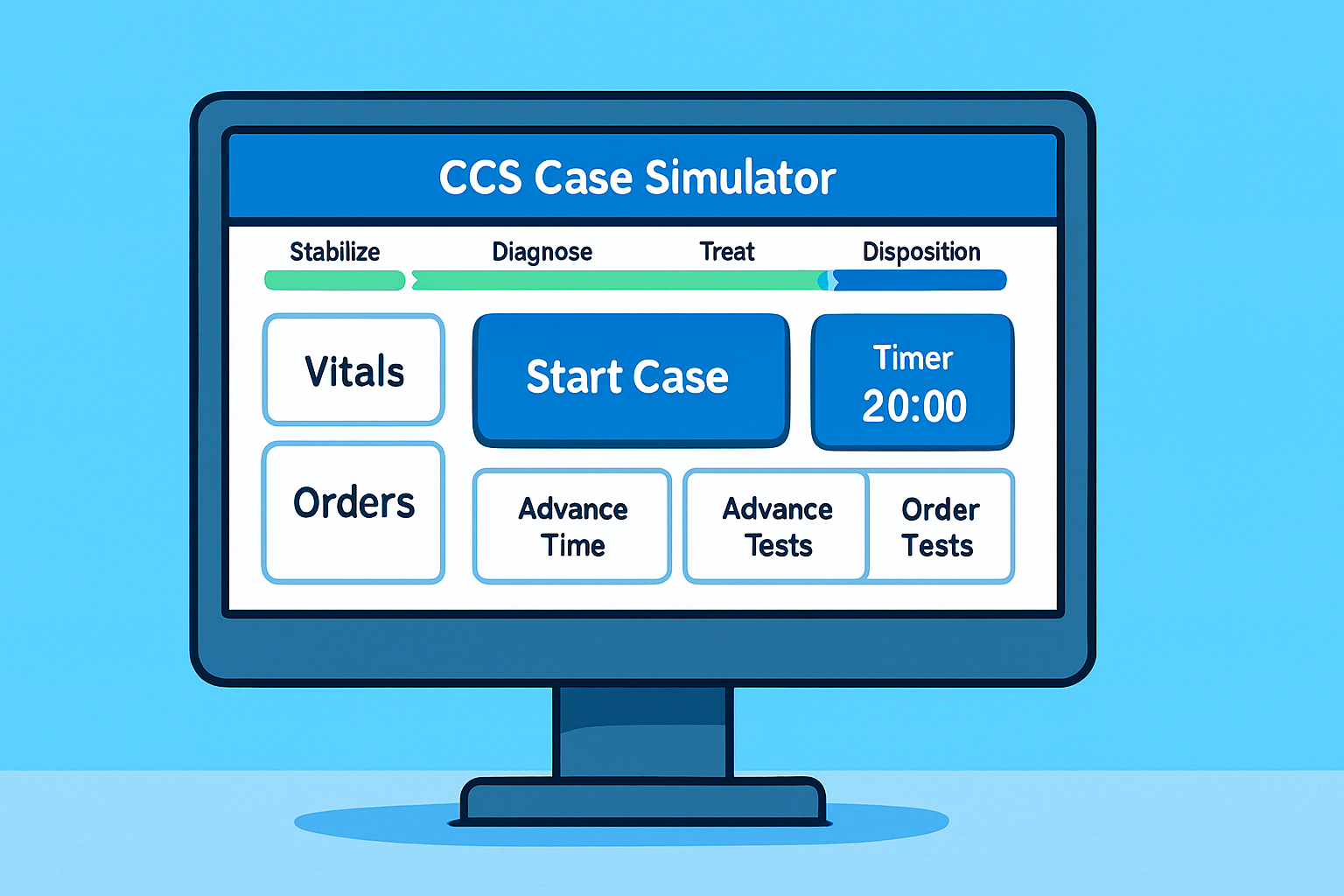

Acute Stroke ED Workflow (Infographic)

Arrival & Triage

ABCs, glucose check, NIHSS assessment

→

Non-Contrast CT

Exclude hemorrhage (target ≤25 min)

→

IV tPA

If <4.5h & no contraindications

Goal: Door-to-Needle ≤60 min

Large Vessel Occlusion?

CTA/CT Perfusion

NIHSS ≥6, ICA/M1/M2 occlusion

→

Mechanical Thrombectomy

Within 6h (or up to 24h if imaging favorable)

4. Intravenous Thrombolysis: tPA Criteria and Contraindications

Alteplase (IV tPA) is the only FDA-approved systemic thrombolytic for acute ischemic stroke. It is indicated in patients presenting within 4.5 hours of symptom onset who have no contraindications. Step 3 vignettes often test recognition of inclusion/exclusion lists, especially nuanced contraindications that are easily overlooked.

| Inclusion Criteria |

Absolute Contraindications |

| Age ≥18 |

Intracranial hemorrhage on CT |

| Ischemic stroke with measurable deficit |

Active internal bleeding |

| Onset <4.5 hours |

BP >185/110 mmHg despite treatment |

| CT excluding hemorrhage |

Recent stroke, head trauma, or surgery (<3 months) |

| NIHSS typically >4 (disabling deficits) |

Known bleeding diathesis, INR >1.7, platelets <100k |

Relative contraindications include seizure at onset, minor or rapidly improving symptoms, or large infarct volume on imaging. Blood pressure must be lowered cautiously below 185/110 mmHg before tPA. A common exam trick is presenting a patient eligible for tPA but with elevated BP; the correct answer is to treat with IV labetalol or nicardipine first, then administer alteplase once criteria are met.

5. Mechanical Thrombectomy: Indications and Workflow

Mechanical thrombectomy has revolutionized stroke care by extending reperfusion beyond the IV tPA window for large vessel occlusions (LVOs). Step 3 questions test whether candidates recognize which patients qualify for thrombectomy, which is performed by interventional neuroradiology using stent retrievers or aspiration catheters.

The key indications are patients with proximal anterior circulation LVO (internal carotid, M1, proximal M2), who present within 6 hours of last known well. With advanced imaging (CT perfusion, CTA), the window extends up to 16–24 hours in select patients with a favorable core/penumbra mismatch. These criteria stem from pivotal trials (DAWN, DEFUSE 3).

- IV tPA should be given first if within the 4.5-hour window — do not delay for thrombectomy preparation.

- NIHSS score typically ≥6 indicates disabling deficits consistent with LVO.

- Rapid CTA or MRA is needed to confirm LVO before thrombectomy transfer.

Exam vignettes may test scenarios where a patient arrives 2 hours after symptom onset with left hemiplegia and M1 occlusion: the correct sequence is to administer tPA immediately (if no contraindications) and then proceed to thrombectomy. Recognizing that these therapies are complementary, not mutually exclusive, is a critical Step 3 point.

6. Secondary Prevention and Post-ED Management

Once reperfusion decisions are complete, secondary prevention is the next critical layer of management. Candidates must select the correct regimen depending on stroke etiology. All patients should receive antiplatelet therapy, typically aspirin, unless they were treated with tPA (where aspirin is delayed 24 hours pending repeat imaging). For minor strokes and high-risk TIAs, dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin + clopidogrel for 21–90 days) may be tested.

Anticoagulation is indicated for cardioembolic sources such as atrial fibrillation. Vignettes test timing: anticoagulation should not be initiated immediately after a large infarct due to hemorrhage risk; instead, it is deferred for 1–2 weeks depending on infarct size. Blood pressure management, statin initiation (high-intensity for all ischemic stroke patients), and diabetes control are also expected interventions.

Workup of underlying etiology includes carotid ultrasound for anterior circulation stroke, echocardiography for cardiac emboli, and vascular imaging when indicated. The exam may test recognition that carotid endarterectomy is indicated for symptomatic stenosis ≥70%, ideally performed within 2 weeks. Candidates should avoid repeating the acute CT unnecessarily unless there is neurologic deterioration, in which case hemorrhagic conversion must be ruled out.

7. Vignette Integration and Special Populations

Step 3 integrates stroke care into realistic case simulations, often embedding comorbidities. Pregnant patients present unique challenges — tPA is not absolutely contraindicated, but risks must be balanced; mechanical thrombectomy is preferred if feasible. Patients on anticoagulants may be excluded from tPA depending on INR or drug timing.

Mimics such as hypoglycemia, seizure with post-ictal Todd paralysis, complicated migraine, and conversion disorder can appear in exam vignettes. Correct first step remains CT to rule out hemorrhage before dismissing as a mimic. Stroke in the posterior circulation (vertebrobasilar occlusion) may present with dizziness, diplopia, ataxia, or locked-in syndrome — scenarios designed to test awareness beyond classic hemiplegia.

Pediatric and young adult strokes, though rare, may appear in Step 3 as zebras. Causes include sickle cell disease, dissection, or hypercoagulable states. Vignettes may ask for exchange transfusion in sickle cell–related stroke or anticoagulation for cervical artery dissection. These outlier cases reinforce the importance of integrating systemic conditions into the acute management algorithm.

8. Pitfalls, Rapid Review, and Exam Pearls

Stroke questions are designed to test both speed and precision. Common pitfalls include ordering the wrong imaging (MRI before CT), delaying tPA while awaiting labs that are not clinically indicated, or inappropriately lowering blood pressure before reperfusion. Remember: hypoglycemia must always be excluded before labeling a deficit as stroke.

Rapid-Review Checklist

- Non-contrast CT is first test — exclude hemorrhage.

- IV tPA: give within 4.5 hours; ensure BP <185/110 mmHg.

- Mechanical thrombectomy: large vessel occlusion, up to 24 hours with favorable imaging.

- Aspirin within 24–48h unless tPA given; then delay until 24h post-tPA.

- High-intensity statin and secondary prevention for all ischemic strokes.

Step 3 board-style cues: If onset time is unknown (e.g., patient awoke with symptoms), tPA is contraindicated unless imaging shows diffusion–FLAIR mismatch. If deficits are rapidly improving, withholding tPA is often the safest answer. For posterior circulation strokes with severe deficits, thrombectomy may still be beneficial if criteria are met. Avoiding these traps and sticking to protocolized pathways is the most reliable approach to high-yield Step 3 stroke questions.

References: AHA/ASA Stroke Guidelines; Powers WJ, et al. 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2019;50:344–418.

100+ new students last month.