Why the USMLE Diabetes Management Algorithm Matters

Effective mastery of a structured USMLE diabetes management algorithm is essential for Step 2 CK and Step 3. Both exams heavily emphasize insulin initiation, adjustments based on patterns, hypoglycemia recognition, and applying guideline-consistent care in ambulatory, ED, and inpatient settings. Students often know the right insulin types but miss questions because they lack systematic reasoning. These items test logic, not memorization—specifically, stabilizing first, then diagnosing, then adjusting therapy in a safe and guideline-driven order.

This article breaks down diabetes management using evidence-based principles, including ADA recommendations, typical board-style titration strategies, and commonly tested clinical reasoning traps. Each section builds perspective on insulin choices, adjustment algorithms, hypoglycemia workflows, and real USMLE-style patient cues. You will also see compact visuals and tables that help solidify patterns, which is how NBMEs structure diabetes questions. Where appropriate, we highlight how MDSteps’ Adaptive QBank and exam analytics can help you master high-yield outpatient endocrine logic by analyzing your misses and converting them automatically into review flashcards.

Basal Insulin: When to Start and How to Titrate

On the USMLE, basal insulin is the correct next step for persistent hyperglycemia despite maximal oral therapy, A1c ≥10%, or symptomatic catabolism. Vignettes often hint with unintentional weight loss, polyuria, and fasting glucose above 180 mg/dL. Exams expect you to know a starting strategy and a titration pathway—not exact dosing, but safe, logical progression. Basal insulin questions frequently require interpreting fasting trends, ruling out overnight hypoglycemia, and applying stepwise titration rules.

| Scenario | USMLE-Appropriate Action |

|---|

| Fasting glucose consistently high | Increase basal by 10–15% every 3–4 days |

| Fasting low but daytime high | Decrease basal; add or adjust mealtime insulin |

| Nocturnal hypoglycemia | Reduce basal by 10–20% |

The key exam skill is recognizing patterns and adjusting the correct insulin type. If fasting glucose is off, you fix basal. If postprandial glucose is off, you fix bolus. Many examinees mistakenly increase basal insulin for global hyperglycemia, but doing so causes morning hypoglycemia—a classic NBME trap.

Prandial and Correctional Insulin: Post-Meal Logic on the USMLE

Postprandial hyperglycemia is among the most testable diabetes patterns. Step 2 CK and Step 3 frequently give case vignettes where basal is correct but rapid insulin is missing or mistimed. The exam wants recognition that mealtime control is independent of fasting control. When adding bolus insulin, the algorithm starts small and titrates based on 2-hour post-meal readings.

An essential high-yield rule: If postprandial glucose is consistently >180 mg/dL, increase mealtime insulin by 10–15% per affected meal. Correctional insulin is used only for short-term adjustments, not as a replacement for real mealtime bolus. In inpatient settings, boards often ask you to abandon sliding-scale–only regimens and initiate a physiologic regimen combining basal, nutritional, and correctional components.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

Recognizing Patterns: The Most Important Skill for Diabetes Questions

All USMLE diabetes management algorithms rely on one principle: treat patterns, not individual readings. Examiners give 3–4 glucose values so you can infer which insulin component is responsible. Pattern recognition is explicitly tested across Step 2 CK ambulatory questions and Step 3 simulation cases, where glucose stabilization is required before advancing to diagnostic steps.

Rising fasting glucose → Problem

- Insufficient basal insulin

- Dawn phenomenon

- Basal needs 10–20% uptitration

Rising post-meal glucose → Problem

- Poor carb coverage

- Missed or late bolus

- Requires bolus titration

MDSteps’ Adaptive QBank is specifically designed to drill these exact pattern-recognition sequences using over 9,000 questions and analytics that highlight your missed categories, which can then be converted into spaced-repetition flashcards.

Hypoglycemia: A Critical USMLE Safety Workflow

Hypoglycemia questions test safety, rapid protocol recognition, and the ability to prioritize stabilization. The USMLE expects a consistent response: check glucose, treat immediately, then identify the cause. Symptoms such as tremor, palpitations, confusion, or behavioral changes must prompt immediate action. Severe hypoglycemia on Step 3 CCS requires IV dextrose or IM glucagon before any diagnostic workup.

| Glucose Level | Immediate Action |

|---|

| <70 mg/dL | Give oral 15 g fast-acting carbohydrate if awake |

| <54 mg/dL (clinically significant) | Immediate glucose + evaluate insulin dosing errors |

| Unconscious or NPO | IV 25 g dextrose or IM glucagon |

A common NBME distractor is ordering labs before giving glucose. Treat first, investigate after stabilization.

Inpatient Insulin Management: Step 2 CK and Step 3 Priorities

Inpatient diabetes questions require separating stable patients from those requiring rapid intervention. Sliding-scale insulin alone is never the correct answer for persistent hyperglycemia. The USMLE expects a physiologic basal–bolus–correction regimen with daily reassessment. Another common exam scenario is switching a patient from home insulin to a weight-based inpatient regimen after admission, especially for surgery or illness.

Steroid-induced hyperglycemia is frequently tested. Look for rising afternoon and evening glucose, and adjust mealtime insulin accordingly. Postoperative patients with fluctuating intake need reduced prandial doses and careful monitoring. Hypoglycemia prevention is prioritized over strict glucose control in hospitalized patients, especially older adults.

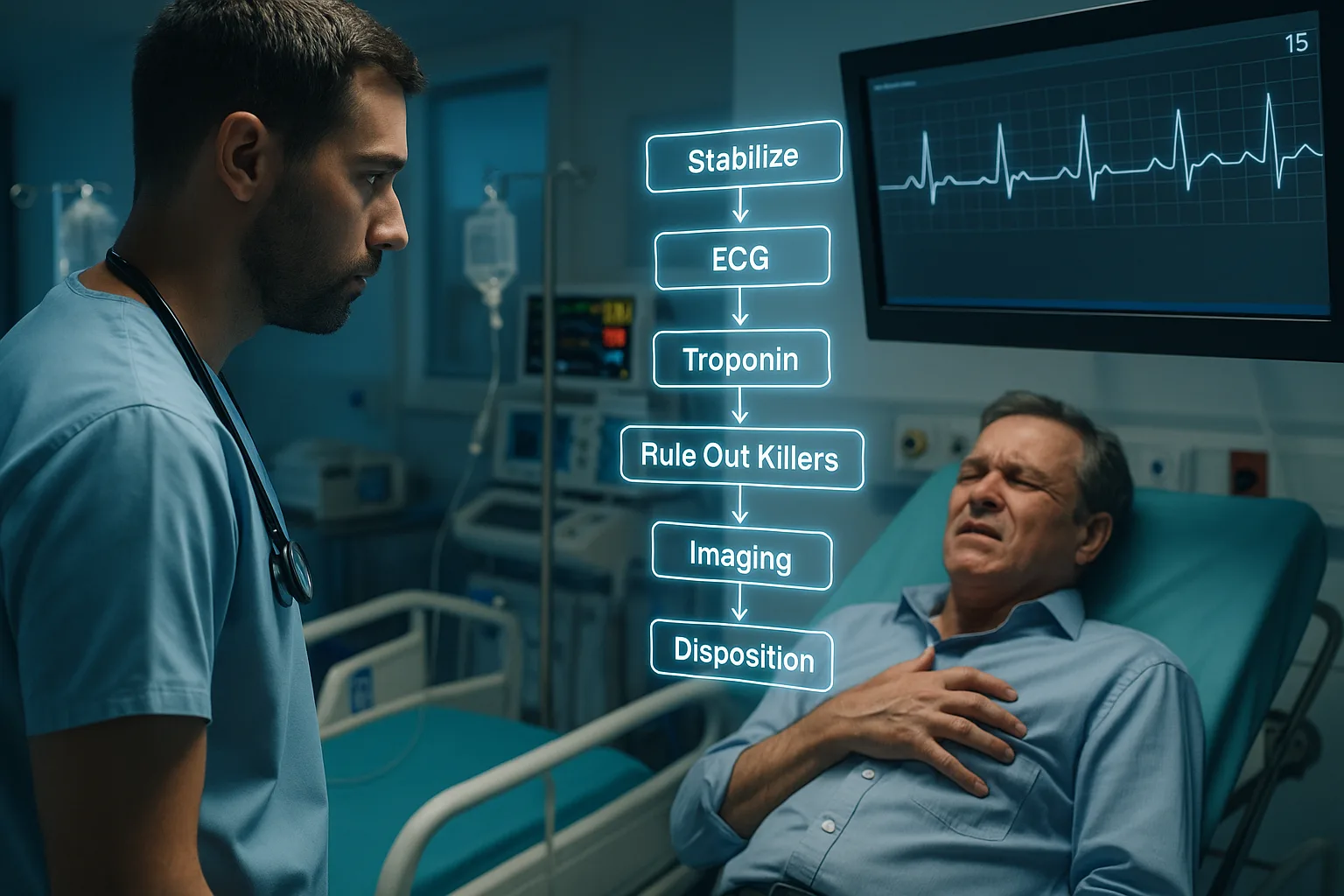

Diabetes on Step 3 CCS: Stabilize First, Then Diagnose

CCS cases explicitly test your ability to stabilize unsafe glucose levels before proceeding with diagnostic steps. The general sequence: correct severe hypo- or hyperglycemia → start appropriate insulin regimen → reassess → address underlying causes. If a case involves DKA or HHS, fluid resuscitation precedes insulin. For routine outpatient diabetes management, CCS cases expect scheduled visits, A1c checks every three months, foot exams, statin therapy, blood pressure control, and nephropathy screening.

Step 3 simulations also frequently test transitions of care. When discharging a patient, you must return them to safe home dosing, ensure follow-up, and avoid aggressive inpatient doses that could cause outpatient hypoglycemia.

Rapid-Review Checklist: What the USMLE Wants You to Remember

- Basal insulin fixes fasting glucose; bolus insulin fixes postprandial glucose.

- Increase insulin by 10–15% for consistent elevated patterns.

- Nocturnal hypoglycemia → decrease basal by 10–20%.

- Sliding-scale insulin alone is never correct for persistent inpatient hyperglycemia.

- Severe hypoglycemia → immediate IV dextrose or IM glucagon.

- CCS: stabilize glucose first, diagnose second.

- A1c ≥10% or catabolic symptoms → start basal insulin.

- Steroid hyperglycemia → adjust afternoon/evening bolus dosing.

References

Medically reviewed by: Alexandra Ruiz, MD, Endocrinology

100+ new students last month.