Understanding the Clinical Logic Behind Headache Algorithms

Headache algorithm mastery is one of the highest-yield skills for the USMLE, especially when distinguishing migraine from life-threatening causes such as subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and meningitis. This guide uses an evidence-driven approach to help you think like the NBME: pattern recognition, red-flag prioritization, stepwise stabilization, and appropriate diagnostic sequencing. Because the exam frequently blends benign presentations with dangerous mimics, you must learn how to rely on objective clues rather than the patient’s single complaint of “headache.”

Within the first 100 words, we anchor our long-tail keyword — headache algorithm for migraine, SAH, and meningitis — and make explicit what you will learn: an integrated diagnostic pathway grounded in real-world clinical logic. Unlike single-diagnosis review articles, this guide builds an end-to-end decision structure that mirrors board-style vignettes, where misinterpreting one detail leads to the wrong next step. You’ll learn how to weigh time course, neurological findings, associated symptoms, and exam red flags.

USMLE items often reward quick identification of syndromic clusters. Migraines follow a predictable chronology and are largely clinical diagnoses. Meningitis presents with systemic illness and fever, while SAH presents as a “worst headache of life” with abrupt onset. But between these archetypes lie pitfalls: meningitis without fever; SAH without loss of consciousness; migraine with neck stiffness; and normal initial CT in suspected SAH. Understanding the algorithm takes you from “what’s possible?” to “what must be ruled out first?”

| Feature |

Migraine |

SAH |

Meningitis |

| Onset |

Gradual, 30–120 min |

Sudden, seconds |

Acute–subacute, hours |

| Key Symptom |

Photophobia ± aura |

"Worst headache of life" |

Fever, neck stiffness |

| Diagnostic Priority |

Clinical |

Non-contrast CT → LP |

LP (after CT if ICP risk) |

As you progress through the algorithm in the sections below, remember that every question places you in a triage role: rule out catastrophic disease before refining the diagnosis. This is identical to how emergency physicians approach headache in real practice.

Later sections also highlight how tools like the MDSteps Adaptive QBank help reinforce diagnostic reasoning through 9,000+ USMLE-style questions with analytics showing tendencies to miss red-flag patterns across headache-related content.

Step 1: Identify Dangerous Headache Red Flags Before Anything Else

Every USMLE headache algorithm begins with one question: Is this presentation potentially life-threatening? Red flags must be evaluated before any consideration of treatments or benign diagnoses. The exam commonly provides multiple clues in rapid succession, and your task is to recognize them as pattern clusters, not individual facts. These “can’t-miss” features prompt immediate imaging or lumbar puncture, and failing to identify them is one of the most frequent NBME trap points.

High-yield red flags can be categorized into temporal, systemic, neurological, and structural warning signs. Sudden onset (“thunderclap”) is the hallmark of SAH. Fever and altered mental status strongly point toward meningitis or encephalitis. Any focal neurological deficit shifts the differential toward hemorrhage, stroke, mass effect, or CNS infection. Immunosuppressed patients require an expanded infectious differential including fungal and opportunistic pathogens. A headache worse when lying flat or worse in the morning suggests increased intracranial pressure.

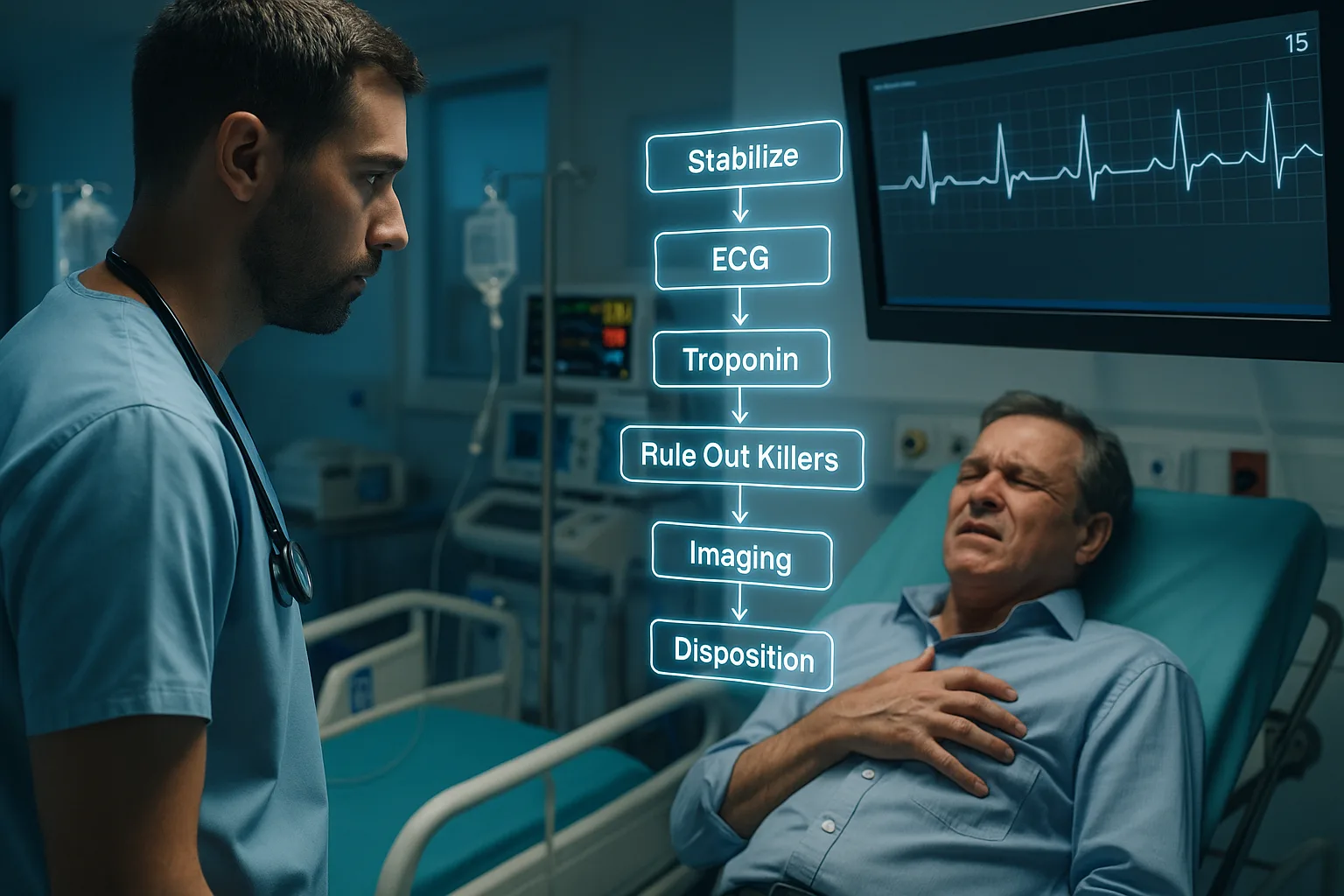

For exam purposes, cluster these red flags into three actionable groups: immediate CT (non-contrast), immediate LP, and CT before LP (ICP concern). The algorithm relies heavily on a safety-first approach. If either SAH or meningitis is suspected, early stabilization (airway, oxygenation, IV access) precedes diagnostic steps, although the exam rarely tests the procedural details beyond ensuring nothing delays life-saving evaluation. Avoiding anchoring bias is essential: many candidates mistakenly default to “migraine variant” in the setting of neck stiffness or nausea, missing catastrophic pathology.

High-Yield Red Flags for the USMLE

- Sudden severe onset (“thunderclap”)

- Fever, photophobia, neck stiffness

- Altered consciousness or confusion

- Immunocompromised state (HIV, chemotherapy, transplant)

- Papilledema or signs of increased ICP

- Focal neurological deficit (except true migraine aura)

- New headache > age 50 (concern for temporal arteritis)

- Headache after exertion or Valsalva

In Step 2 CK and Step 3 vignettes, the presence of any red flag usually means you should not diagnose migraine without imaging or LP. This is a classic NBME trap: the patient describes “photophobia” (seen in both meningitis and migraine), but the key differentiator may be fever or neck stiffness mentioned only once.

Step 2: Distinguishing Migraine — A Diagnosis of Pattern, Not Exclusion

Migraines are frequently mis-handled in USMLE questions because students incorrectly approach them as “diagnoses of exclusion.” Instead, migraine is a diagnosis of recognition supported by typical chronology, associated sensory symptoms, and predictable relief patterns. When the question stem fits cleanly into the pattern of recurrent unilateral throbbing pain lasting hours with photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and possibly aura, the algorithm favors migraine — provided red flags are absent.

Remember that migraine aura characteristics are consistent and reversible. Visual aura (scintillating scotoma) is classic. Sensory auras appear as tingling or numbness that spreads gradually. Sudden onset deficits are not migraine auras. USMLE question writers deliberately introduce inconsistencies (e.g., aura lasting >60 minutes or beginning after the headache) because these suggest alternative diagnoses like TIA.

Management depends on timing and severity. For mild-moderate migraine, NSAIDs and triptans are appropriate. Triptans are avoided in patients with CAD, pregnancy, or uncontrolled hypertension (per guidelines). Status migrainosus requires IV antiemetics, IV NSAIDs, or dihydroergotamine. Preventive therapy is indicated for ≥4 disabling headaches per month and includes beta-blockers, topiramate, CGRP antagonists, or TCAs.

On the exam, avoid ordering CT scans unnecessarily. If the vignette reads like a classic migraine in a young healthy patient with no red flags, imaging is not required. Likewise, lumbar puncture is inappropriate without concern for infection, SAH after negative CT, or atypical symptoms. Step exams reward knowing when not to test.

Master your USMLE prep with MDSteps.

Practice exactly how you’ll be tested—adaptive QBank, live CCS, and clarity from your data.

What you get

- Adaptive QBank with rationales that teach

- CCS cases with live vitals & scoring

- Progress dashboard with readiness signals

No Commitments • Free Trial • Cancel Anytime

Create your account

Step 3: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage — The Thunderclap Emergency

SAH is tested across all USMLE levels because its diagnostic logic is algorithmic. The hallmark symptom is sudden onset severe pain described as the “worst headache of life,” peaking within seconds. This abruptness is more important than severity. Additional clues include vomiting, neck stiffness, photophobia, transient loss of consciousness, or focal neurological deficits. Risk factors such as uncontrolled hypertension or family history of aneurysm heighten suspicion.

The correct diagnostic sequence is non-contrast head CT as the first step. Sensitivity approaches 95% in the first six hours but decreases over time. If CT is negative and suspicion remains high, lumbar puncture is mandatory. The boards test your ability to recognize xanthochromia (yellow-tinged CSF from bilirubin) as the key finding. RBC count that does not clear across tubes also supports SAH.

Management always begins with stabilization and blood pressure control (target systolic <140 per guidelines). Nimodipine is required to prevent vasospasm. Neurosurgical consultation is immediate for aneurysm repair. Never give anticoagulation or thrombolytics. These principles are consistently tested.

Step 4: Meningitis — When Infection Mimics Migraine or SAH

Meningitis is a frequent distractor in USMLE headache questions because it overlaps with both migraine (photophobia) and SAH (neck stiffness). The classic triad is fever, neck stiffness, and headache — but only a minority present with all three. Altered mental status, petechial rash (Neisseria), or recent sinusitis/otitis are strong contextual clues. Immunocompromised patients require broader coverage, including Listeria.

The algorithm: if there are no signs of increased ICP or focal neurological deficits, perform LP immediately. If there is papilledema, new focal deficits, or seizures, obtain CT before LP. Blood cultures must be obtained promptly, but empiric antibiotics cannot be delayed while waiting for imaging.

Empiric therapy depends on age group and risk factors. Ceftriaxone + vancomycin is the backbone for adults, with ampicillin added when Listeria risk is high. Dexamethasone is recommended for pneumococcal meningitis. Understanding gram stain patterns remains high-yield for Step 1 and Step 2 CK. The boards may also test glucose, protein, and opening pressure profiles, particularly for differentiating viral, bacterial, and fungal meningitis.

Step 5: Integrating the Algorithm — A Unified Decision Pathway

At this stage, the algorithm becomes simple: classify based on onset speed, systemic signs, neurologic deficits, and safety triggers. Most USMLE headache questions follow a predictable branching structure, though details are intentionally varied to avoid memorization-only approaches. This is why building fluency through adaptive practice matters.

| Branch Point |

Action |

| Sudden onset, maximal at start |

CT head → LP if negative |

| Fever/meningeal signs |

LP (unless ICP concern → CT first) |

| Recurrent stereotyped headaches |

Clinical migraine diagnosis |

| Immunocompromised or focal signs |

CT → LP; broaden infectious differential |

As you refine this logic using real questions, platforms like the MDSteps Adaptive QBank can surface your red-flag misses through performance analytics. If your data show a recurring pattern — e.g., mistakenly labeling early meningitis as migraine — the auto-generated flashcards and spaced repetition decks help reinforce those weak points.

Step 6: Common NBME Traps and How to Avoid Them

USMLE exam writers do not test rare diseases nearly as often as they test your ability to avoid diagnostic error. The most common trap is assigning migraine prematurely because the patient mentions photophobia. But photophobia occurs in meningitis too — the context matters. A patient who appears ill, febrile, or confused cannot have migraine until proven otherwise.

- Trap: Negative CT excludes SAH. Reality: If suspicion is high, LP is required.

- Trap: Neck stiffness means meningitis. SAH commonly produces meningeal irritation.

- Trap: CT before LP always. Only when ICP risk or focal deficits exist.

- Trap: Focal deficits exclude migraine. Aura may include transient sensory or visual deficits but not sudden paralysis.

- Trap: Viral symptoms mean benign disease. HSV encephalitis and bacterial meningitis may begin with nonspecific prodrome.

Mastering these traps strengthens your overall diagnostic discipline, increasing accuracy under timed conditions.

Step 7: Rapid-Review Checklist for Exam Day

- Thunderclap → CT → LP if negative → manage SAH

- Fever + neck stiffness → LP unless ICP concern

- Meningitis suspected → never delay antibiotics

- No red flags + stereotyped pattern → migraine diagnosis

- CT before LP only when focal deficits or papilledema present

- Xanthochromia = SAH even if CT normal

- Opening pressure elevated in bacterial meningitis

- Migraine aura evolves gradually; SAH deficits appear abruptly

References

Medically reviewed by: Jonathan Reyes, MD, Neurology

100+ new students last month.